The Best of the Rest: Species Highlight

If you’ve paid any attention to the Long Island Pine Barrens Society these past two years, you’re sure to have heard of “The Best of the Rest” initiative. This campaign seeks to complete the promise of the 1993 Pine Barrens Protection Act by preserving another 3,800 acres of land. If you’re curious as to the status of the campaign, head on over to this page on our website. While preserving untouched land for its own sake is all well and good, today we’re going to highlight some of the animals which can be found in these “The Best of the Rest” properties, and why preserving their habitat is crucial for their wellbeing.

Monarch Butterflies

Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus) are a beloved insect, and for good reason. Their beautiful coloration sets them head and shoulders (proverbially speaking) above the rest of the insect world. Although on a global scale the species is faring well, the migratory populations (such as New York’s) are listed as Vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), meaning they’re the most at-risk species we’ll be discussing today. Of course, the main source of these butterflies’ decline is the decline of suitable sources of nutrition. Wildflowers like milkweed (which you can, and should, plant in your own backyard) are crucial for this. Another such flower is known as Butterfly Weed, and is prominently found in the Rocky Point area we are seeking to protect. Nineteen (19) of the 60 acres that are included in “The Best of the Rest” plan are currently eyed by the DEC, but if all 60 acres are preserved it would go a long way in preserving this vital resource for monarch butterflies, creating a safe harbor for them on Long Island.

Grasshopper Sparrow

While the IUCN lists the Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum) as one of Least Concern, it is a species with a range covering most of the continental United States and stretches south into Mexico. Thus, there are numerous subspecies and populations, many of which, taken on their own, are threatened. Here in New York, the species is listed as one of Special Concern, as the local population has declined considerably in recent years. As the name suggests, this species of sparrow is fondest of grassland habitats, and specifically can be found on the EPCAL property. This extensive grassland is owned by the Town of Riverhead; it is as of yet entirely unpreserved. Along with the Shoreham forest and the Rose-Breslin properties, this is one of the chief areas of interest for The Best of the Rest” initiative.

Eastern Meadowlark

Sticking with the EPCAL property, another beautiful bird species that can be found there is the Eastern Meadowlark (Sturnella magna). Throughout the year, this bird’s range can extend from Canada to Mexico, and from Texas to the coast of the Atlantic Ocean. Yet, it is listed as a Near Threatened species by the IUCN, due to population decline caused by loss of habitat. The DEC specifically highlights Long Island as a location where development is impacting the population. As the name suggests, meadowlarks prefer wide open grasslands, much like the grasshopper sparrows, and so the preservation of the EPCAL property is crucial in maintaining one of Long Island’s quintessential ecosystems, and the creatures that inhabit it.

This was just a brief glimpse of some of the animals whose conservation status would be improved should the entirety of “The Best of the Rest” properties be preserved. If you’re not already, consider following the Long Island Pine Barrens Society’s Facebook and Instagram accounts where, in the coming weeks, we’ll be discussing these species, and many more that “The Best of the Rest” initiative seeks to protect.

By Travis Cutter, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Posted on July 20, 2024 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Middle School Kids Go To College 2024 Recap

For over a decade, the Long Island Pine Barrens Society has provided Long Island’s middle school students the opportunity to be scientists, thanks to sponsorship from the National Grid Foundation. Each year, this program allows dozens of students to learn more about Long Island’s water, how to preserve it, and how to think like scientists to solve problems.

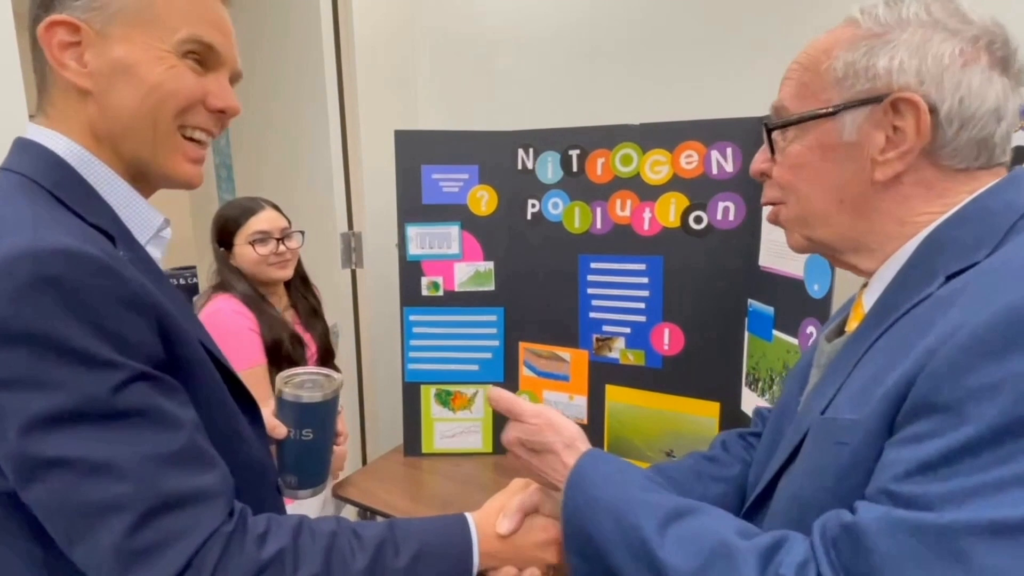

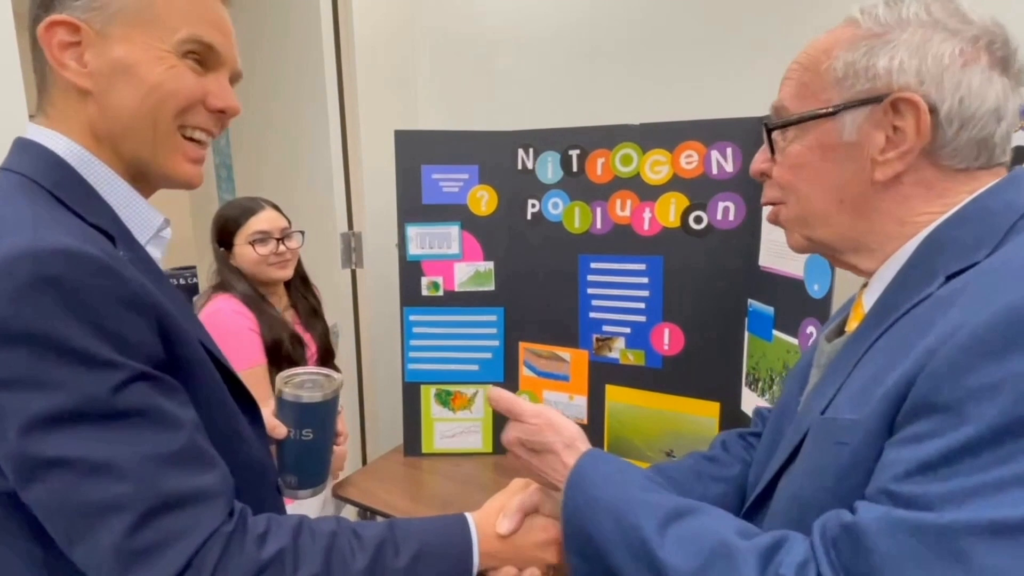

It all starts in the classroom. At the start of the year, students spend time learning about Long Island’s water, what threats face it, and what can be done to preserve it. Then, the training wheels are removed, and the students are let loose to think about a problem facing Long Island’s water, and how they’d best solve it. Students are tasked with doing research, writing papers, and preparing poster presentations summing up their work, which are presented to Long Island Pine Barrens Society staff at each school’s “Water Day.” This year, three classes of Patchogue-Medford middle school students – from Oregon, Saxton, and South Ocean Middle Schools – presented their work. Topics ranged from microbeads and other harmful plastics, to nitrate pollutions and the “dead zones” that appear in the Long Island Sound, to problems found in the home, such as the efficacy of water filters.

While last year featured the program’s return to an in-person experience in the wake of the pandemic, this year featured a never-before-implemented addition to the program: a hike! Over three dozen students were given a guided hike through Fish Thicket Preserve – a Town of Brookhaven park which was preserved only thanks to the advocacy of Pat-Med students of yesteryear – where LIPBS board members John Turner and Bob McGrath taught about the local Pine Barrens ecosystem, and the history of the preserve. By the day’s end, the students were more engaged than ever before with the environment, and that alone is the mark of a successful program.

A month after the three Water Days and the hike through Fish Thicket Preserve, all the students traveled to Stony Brook University, where they were treated to a lecture by Dr. Christopher Gobler, the premier expert on Long Island’s water quality. For forty minutes, Dr. Gobler provided students with a college-level presentation, talking in detail about the various contaminants that threaten our water, as well as what solutions are being worked on to improve things. Then, the students once again presented their work to LIPBS staff as well as members of the Center for Clean Water Technology.

Finally, the program wrapped up on June 8th, at Wertheim National Wildlife Refuge. There, students were presented with certificates recognizing their efforts, and the students who worked on the projects deemed the best by the LIPBS were presented with certificates from Deputy County Executive Jennifer Juengst and Alice Painter, Chief of Staff to Assemblyman Joe DeStefano. (Plaques provided by the National Grid Foundation recognizing these winning students’ achievement were delivered subsequently). Students were again given time to present their work to the LIPBS, government representatives, and of course their families. After affording guests the time to talk to the students about their work, board member Bob McGrath led a hike through Wertheim, where he expounded on the effect the Carmans River watershed has on the ecosystem, the quirky nature of the White-breasted Nuthatch, and, of course, ticks (who made sure to attend the hike!).

The Middle School Kids Go To College program is perhaps a prime example of what the Long Island Pine Barrens Society is all about. In fostering a love of Long Island’s natural beauty in our youth, we engender a new generation of preservers who will continue the good fight in conserving what makes our Island so special to begin with. In pushing students to their academic limits, we prepare them to rise to the challenge of understanding and protecting the Pine Barrens. And in honoring their achievements, we celebrate the fact that progress is made not by the movement of governments or corporations, but instead by the hard work of individuals.

This year, the Middle School Kids Go To College program was better than ever, and here’s to many more years of reaching ever greater heights!

By Travis Cutter, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Posted on June 20, 2024 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Why Land Preservation is Necessary

If you’ve been following the Long Island Pine Barrens Society’s social media accounts (facebook.com/PineBarrensSociety and @lipinebarrens on Instagram) then you’ve probably seen at least one of our recent posts detailing the status of our “The Best of the Rest” initiative. This initiative’s goal is the preservation of another 3,800 acres of Pine Barrens land, to complete the preservation project begun in 1993 with the passage of the Pine Barrens Protection Act. Odds are, if you’re reading this blog, you’re already on board with this idea. But believe it or not, there are people who might not be on the same page. This blog is thus going to answer, as succinctly as possible, the simple question, “why is land preservation necessary?”

I’ll skip the sappy, sentimental stuff about nature having inherent value – I believe it does, and I’m sure most folks reading this do, too, but it’s a position that veers firmly into the realm of moral philosophy. That feels too esoteric and too grand in scope for this blog post, but perhaps it’s something we’ll return to in the future. Instead, I want to focus on some of the practical, tangible facts that illustrate the benefits that land preservation has both for the wildlife that lives in said land, and the humans who live around it.

First, habitat fragmentation can pose a serious risk to many of Long Island’s terrestrial and semi-aquatic animals. A perfect example of this is the Eastern Mud Turtle, a semi-aquatic reptile which largely resides in bodies of water. If its present habitat dries up, though, the mud turtle will move on foot to a new body of water. Odds are, you’ve seen turtles try to cross a road before, and hopefully you’ve done the right thing and escorted the critter to the where it’s going. But, if there was no development at all, imagine how much easier it would be for the turtles to get where they were going. Thus, preserving as much land as possible ensures the existence of as much continuous habitat as possible, allowing for animals to more easily travel from place to place and deal only with the risks naturally posed to them – and not the horror of an 18-wheeler speeding at them at 60 mph.

An Eastern Mud Turtle in its natural habitat.

Now, let’s talk about something that benefits not just the critters, but also every Long Islander: water. If you didn’t know, water is necessary to life, and here on Long Island, we have remarkably clean, safe water (relative to much of the rest of the country). Why is that? The Pine Barrens of course! While one half of the “Pine Barrens” name comes from the sort of tree that dominates the region, the other half comes from the fact that the soil throughout is remarkably nutrient poor. It is for this reason that the Pine Barrens were left untouched by early settlers, as the land was absolutely useless for farming. And yet, this barren, rocky soil has another purpose: it acts as a natural filter. Thus, when water (such as from rain) seeps into the Pine Barrens soil, it trickles down into the ground, and as it does, much of the particulate matter contained within is filtered out by the soil. Beneath the Pine Barrens lies a vast aquifer, which is where we source our drinking water from. Since the aquifer lies underground, the more pollutants that reside on the surface, the more likely it is that contaminants can seep down into it. If too much land in and around the Pine Barrens is developed, then there’s that much more land that is subjected to constant pollution. Thus, the more land that’s preserved, the more the aquifer is protected, and our drinking water supply will remain all the purer.

A diagram of Long Island’s aquifers.

This is merely a taste of the benefits that land preservation provides. From the point of view of the humblest turtles, to the big picture perspective of human infrastructure, there’s all the reason in the world to preserve as much land as possible. A healthier Long Island means happier, healthier Long Islanders, after all!

Posted on May 20, 2024 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Book Recommendations for New Perspectives

As the weather gets warmer, few things are more alluring than hunkering down in the shade of a pitch pine and reading a good book. If that sentiment is true for you, then perhaps you’d be interested in some off-kilter book recommendations. The selection of books below seeks to be a collection of tales that look at the natural world from different perspectives than you might be used to, and will hopefully give you a newfound appreciation and respect for our wondrous planet.

Recommendation #1: The Histories by Herodotus

Hear me out on this. I’m sure that the first question that popped into your head was “Why a history book recommendation from an environmental nonprofit? Let alone the first ever history book…” Well, that’s just it: despite the title, Herodotus’s classic isn’t just a history book. In writing about the conflict between the ancient Greeks and Persians, Herodotus set the stage by describing in exhaustive detail all the civilizations that he knew about. Thus, the first half of the book reads more like a travelogue, with intricate details provided about the history, culture, and, yes, the environment of the places discussed. From the lush floodplains of the Nile to the barren steppes of the Caucuses, Herodotus paints a vivid (albeit, often embellished) portrait of a world so far removed from our own, yet very akin to it in many ways. If nothing else, Herodotus is a master of empathy, and we could all use a bit more of that in this day and age.

A mountain peak in Ushguli, Georgia. Photo courtesy of Wiley Wilkins, via Unsplash.

Recommendation #2: Butcher’s Crossing by John Williams

This book is perhaps the greatest argument in favor of the “humans should leave nature alone” case ever written. A rebuke of Emersonian transcendentalism, Butcher’s Crossing tells the story of a young man who drops out of Harvard so that he can travel out west to find God. He signs himself up as part of a buffalo hunting crew, and from then on, the book is a never-ending barrage of trauma and hardship, all of it ultimately caused by human greed and the need to assert dominance over the natural world. This book is many things: a western; a critique of human expansionism; a portrait of both the transcendent beauty and the awe-inspiring destructive power inherent in the natural world. It’s a book that ultimately forces self-reflection, and a newfound respect for the world beyond the walls. Be warned, though! This book is not for the squeamish. Guts and gore aplenty, so be wary.

Buffalo. Photo Courtesy of Romain De Moor via Unsplash.

Recommendation #3: Eye of the Albatross by Carl Safina

Odds are, if you’re a dedicated enough conservationist that you read this blog, you’ve heard of Carl Safina. A year ago, in fact, Board Secretary Nina Leonhardt recommended one of his recent releases, Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel, but for this list it only seems appropriate to recommend Carl’s debut work. Eye of the Albatross gives the reader a new perspective, in the most literal sense possible, by following the life of an albatross over the course of a breeding cycle. The life of an albatross, it turns out, is filled with just as many trials and tribulations as the life of a human being. After reading this book, you’ll never look at a bird – or, hopefully, any animal – the same way again.

An albatross. Photo courtesy of Nareeta Martin via Unsplash.

Hopefully at least one of these recommendations suits your fancy this spring! With the world around you reviving after the cold, dreary winter, there’s no better time than to give yourself a new outlook on life, and books are a great way to do that.

By Travis Cutter, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Cover Image courtesy of USGS via Unsplash.

Posted on April 20, 2024 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

A Beginner’s Guide to Bird Identification

For many, birds are the highlight of their time in the Pine Barrens. Yet, even after years of casual birding, it can be difficult to distinguish certain species from one another. That is, of course, if you don’t know what traits to look for. Here, I’ll present for your viewing pleasure some of the more confounding common birds, and how I’ve learned to tell them apart after four years of birding.

Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers

Let’s start with a deceptively simple one. At a glance, the Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers look like they’re the same species, especially at a distance. While the animal’s overall size is usually a good clue as to what species you’re looking at, there are times when this just won’t cut it. The smallest Hairy and the largest Downy could easily appear to be one another! When you’re unsure, the easiest solution is to look at the size of the bird’s beak, and more specifically its size in relation to the animal’s head. If the beak is much smaller than the bird’s head, it’s a Downy. If the beak is as long as or longer than the bird’s head, it’s a Hairy!

Left: A Downy Woodpecker. Right: A Hairy Woodpecker. Photo Credits: Joshua J. Cotten (via Unsplash) and Daniel D’Auria

Yellow and Pine Warblers

Did you know that many of the most common warblers you’ll see around Long Island all belong to the same genus. Yellow, Pine, and Yellow-rumped warblers, among others, all belong to the genus Setophaga. For reference, when we talk about dinosaurs, we generally only refer to an animal’s genus, as distinguishing between species is often too difficult! This holds true with modernity’s warblers, which often possess similar, if not identical, silhouettes. However, with decent lighting, most of the more common species are simple enough to distinguish from one another thanks to their varied plumage patterns. Even with the often-extreme sexual dimorphism present in many warblers, the males and females of a given species are often distinct from any other species you’ll find in a similar habitat (though the drabber females will likely require a closer look to properly identify). However, Yellow and Pine Warblers are an exception to this: they’re both predominantly yellow in coloration and possess darker wings and streaks on their bellies. Ultimately, there are three key features you can use to distinguish the birds. First, are their wings. While Yellow Warblers’ wings are generally darker in coloration than the rest of their body, they’re not the pure gray that Pine Warblers possess. Furthermore, Pine Warbler wings feature distinct white wing bars. Second, the streaks on Yellow Warbler bellies are much clearer and more pronounced than those of the Pine Warblers, which are often smudgy. Finally, Pine Warblers have black eye-lines that, while fainter in color, connect their eyes and their beaks.

Left: A Yellow Warbler. Right: A Pine Warbler. Photo Credits: Patrice Bouchard (via Unsplash) and Fritz Myer

Sparrows

Unlike warblers, which generally each possess distinct coloration or plumage patterns, most sparrows you’ll find on your hikes will be shades of brown, will have some sort of eye line, and will likely have streaks on their bellies. Dark-eyed Juncos and Eastern Towhees are an exception to this, but often you’ll have to rely on traits other than plumage to determine what you’re looking at. Size is useful for identifying Fox Sparrows (large) and Chipping Sparrows (small) but in isolation it can be challenging to place what you’re looking at in perspective with other sparrows you’ve seen. Thus, size is most useful when multiple species are present at the same time.

Habitat is also a clue – you’re unlikely to see a Swamp Sparrow in the heart of the Pine Barrens, after all! When it comes down to it, the most similar sparrows in terms of plumage, habitat, and size are the Song Sparrow and the White-throated Sparrow. Although the latter’s name might suggest a simple way to distinguish the two, this isn’t always the case. Juvenile White-throated Sparrows possess less distinct white throats, to say nothing of natural differences in pigmentation. Not every bird you’ll see out in the field looks like the picture-perfect specimen in your field guide or on the Merlin app. Thus, the most important thing to remember is that Song Sparrows possess very clear and distinct streaks on their belly, and often feature a single, most prominent streak on their centers. Additionally, White-throated sparrows migrate away from the Island during the warmer months, so if it’s the middle of July, you’re not likely to see them.

Left: A Song Sparrow. Right: A White-Throated Sparrow. Photo Credits: Matthew Schwartz and Joshua J. Cotten (both via Unsplash)

Hopefully this brief guide will help you to identify birds and enjoy this incredibly exciting and enriching hobby. From your own backyard to the Shoreham Forest, you can find birds of all shapes and sizes across Long Island, if only you choose to look for them. Happy Birding!

By Travis Cutter, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Posted on March 20, 2024 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Finding a Seat in The Pine Barrens

If you’ve hiked across the Island at all, you’ve probably noticed that seating options tend to range fairly widely across different parks and trails. Your average seating accommodation can range from a full-sized picnic bench to nothing more than the ground beneath your feet. If you’re not already an experienced hiker, going for upwards of an hour along a dirt trail can be tiring, regardless of the general health benefits. In these situations, finding somewhere to rest and take a break can be incredibly important to preserving your energy, and to prevent soreness the next day. So, we wanted to take some time here to go over some methods of catching a break on the seatless trails.

Push up against a tree

If you need a quick rest and there aren’t any benches in sight, your next best option is to take a rest up against a tree. Just having something to put your weight on can take a massive load off your legs, and a tree is perfect for that. It’s worth it to give the tree you choose a quick once-over for any bugs though, since you are about to be leaning against their home. If you’re on a more urban trail, there may even be railings or street signs you could do this with, though it’s unlikely that such a developed trail wouldn’t have a few benches along the way. Whatever you decide to lean against though, this method is ideal if you want to give your legs a short break without stopping completely.

Bring a chair

This one is really more for those extra long trails on the Island, where you’re already going to be keeping a backpack full of snacks and water with you. Especially now, portable “hike chairs” have become more compact and reliable than ever before. They can get to be as small as 1 pound in weight and can easily fit into a backpack for those who need a more defined seat on their hikes. That said, this is the one option here with a fairly steep price. If you want a good chair that’ll last, it’ll cost you well over $100, and even the cheapest chairs won’t come in under $25. And frankly, if you’re going to be hiking such a long trail in the first place, you’re probably already used to going the distance, or at the very least sitting on the ground, and a chair will just take up space.

Photo by Zara Walker on Unsplash

Park yourself in the dirt

Desperate times call for desperate measures, and if you’re too tired to stand, there’s no shame in dirtying your bottom to take a rest. That said, you don’t want to park yourself just anywhere. Especially in warmer months, ticks will be abundant on LI trails, and the last thing you want is to get swarmed by them or other bugs when you sit down.

The best way to avoid ticks, and bugs in general, is to try and find as open a patch of ground as possible. No plants or branches, no grass, and if possible as few leaves as possible. That may sound like a description of the middle of the trail path, but you’d be surprised what corners you can find when you’re really desperate. That said, if you struggle to feel safe doing this, and know you’ll need a break along a benchless trail, it may be worth it to pack a small cloth towel to use as a ground cover. Flour sack towels are best for this, since they can easily fit into your pocket, and provide a fairly large surface to sit on. In colder months you could also use your coat or sweater for this, just be sure to shake it out before putting it back on!

A fine bit of dirt

If all else fails though, and you find yourself needing to sit in an uncleared space with nothing between you and the ground, be sure to follow our guides for tick prevention and identification, check yourself as soon as you get up, brush off your clothes, and take a shower as soon as you get home, before checking yourself again.

However you choose to take a rest along the trail, it’s important to recognize your own limits, and to pace yourself with your hikes. If you’re just starting out and don’t have much experience on the trail, consider starting with a local green trail. These almost always have benches every few hundred feet, and are spacious enough that even in the worst case scenario you can just park yourself on the side of the path, well out of the way of other walkers or cyclists. If you’re really in the mood for a more rugged trail, pick a short one, and don’t dive headfirst into a 5-mile trail loop. Hiking has lots of benefits, both health- wise and in letting you see so much more of nature, but none of that is worth it if you’re suffering every step of the way. Hike safely, hike responsibly, and most importantly, hike at your own pace.

By Andrew Wong, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Posted on February 20, 2024 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Climate Crisis on Long Island

If you’re in any way involved in environmental protection efforts, then you’ve already seen the news that 2023 was the hottest year on record in 150 years, or rather, the hottest year on record since we started keeping records of temperature. Those who haven’t seen this news already can find a plethora of articles from just about every major news publication, but we’ll just link the article from Reuters here. I doubt anyone reading this needs any convincing as to the severity of the climate crisis, so I won’t bother going over the broader aspects of it. What I think will be useful though, is just how this is currently affecting, and will continue to affect Long Island in the coming months and years, so that you can be informed, and so that you can inform others.

Not Retreading Old Ground

The LIPBS has already published an article on how climate change affects the Island, and if you want to do so you can read it here. The points covered can, now, seem almost simple in how normalized they’ve become. Even if it’s not a hurricane we’re dealing with some manner of destructive storm almost every month now, even just this month! The problems listed here are all still happening, but most have already accelerated, or been worsened.

Photo Credit: DEC Helicopter Survey

We’re not here to discuss what we’ve already gone over, and we’re certainly not here to reiterate points all of us already know, so we’ll be leaving this article alone for the time being.

Droughts and the Aquifer

While we were able to avoid a severe drought last year, most of us I think were somewhat caught off guard by the 2022 drought, which came with a while host of recommendations from the water authority to reduce our usage. Of course, 2022 was just the culmination of a series of droughts stretching back to summer 2020, with 2023 being the exception to this. Droughts have, of course, been ongoing on the Island since 2016, with subsequent years only intensifying an issue that was once far from our minds.

Photo Credit: Anton Ivanchenko via Unsplash

When our life here on Long Island is already so dependent on what little water resources we have, droughts occurring so frequently are an issue we cannot afford to ignore in any capacity. This is, of course, not even considering the already occurring contamination of the aquifers, making this at-risk resource so much more delicate. Seawater contamination is at the forefront of this, where rising sea levels and constant droughts only serve to further intensify the problem. Then there is the issue of pollutants entering the ground, which is an entire can of worms itself that could take up an entire blog all on its own. The danger of a drought is very real and is contributing to an issue that only our grandchildren will live to see. Long Island losing its clean source of water is now a very real threat that many of us may very well live to see.

What have we been doing about it?

Issues like this are quickly reaching a point of being too much to handle, but what can be done at this point? For decades, every environmental group has called for these issues to be addressed at a legislative level, yet for every victory, it comes with a plethora of losses. Even the Pine Barrens Protection Act, which marked such a massive victory in 1993, today is sometimes little more than a suggestion to big developers like Discovery. So then what course of action remains, if even our greatest victories are sometimes compromised?

Consider the decades of nonviolent action that have failed to produce results the next time you hear about an activist acting out in front of a government building, or about the interruption of some awards you looked forward to by people screaming in the planet’s name. Consider the fact that the very first widely reported eco protest happened 54 years ago, and how we’re on an even faster course to environmental destruction now than we were then. That for all our peaceful efforts, the forces that are polluting our water and planet have more power today than they ever have before. It’s easy to distance yourself from the most extreme protestors and advocates, who are willing to put their livelihoods on the line so easily for their causes. Even easier than to condemn their actions as too extreme, or the wrong way to do things. But when the right way of doing things has gone so long not only without results, but with a constant downward trend, then what reason is there to continue doing things the right way?

The environmental movement has a long history of victories, but very few of them directly affect the quality of life for the people around it. Despite the researched and confirmed health benefits of living in or around green areas, a lovely trail does little to help those living in poverty. It’s only in recent years that the topic of Environmental Justice has come closer and closer to being a core part of the movement. Environmentalism as a cause cannot survive so long as it tries to push itself above more ground level social causes. As long as housing inequality exists, as long as income inequality exists, as long as race inequality exists, and as long as our economic system rewards the rampant destruction of the planet, no lasting change will be made. As social justice movements expand and move towards the future, the environmental movement needs to move with them, lest we be left behind in the dust.

By Andrew Wong, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Posted on January 30, 2024 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

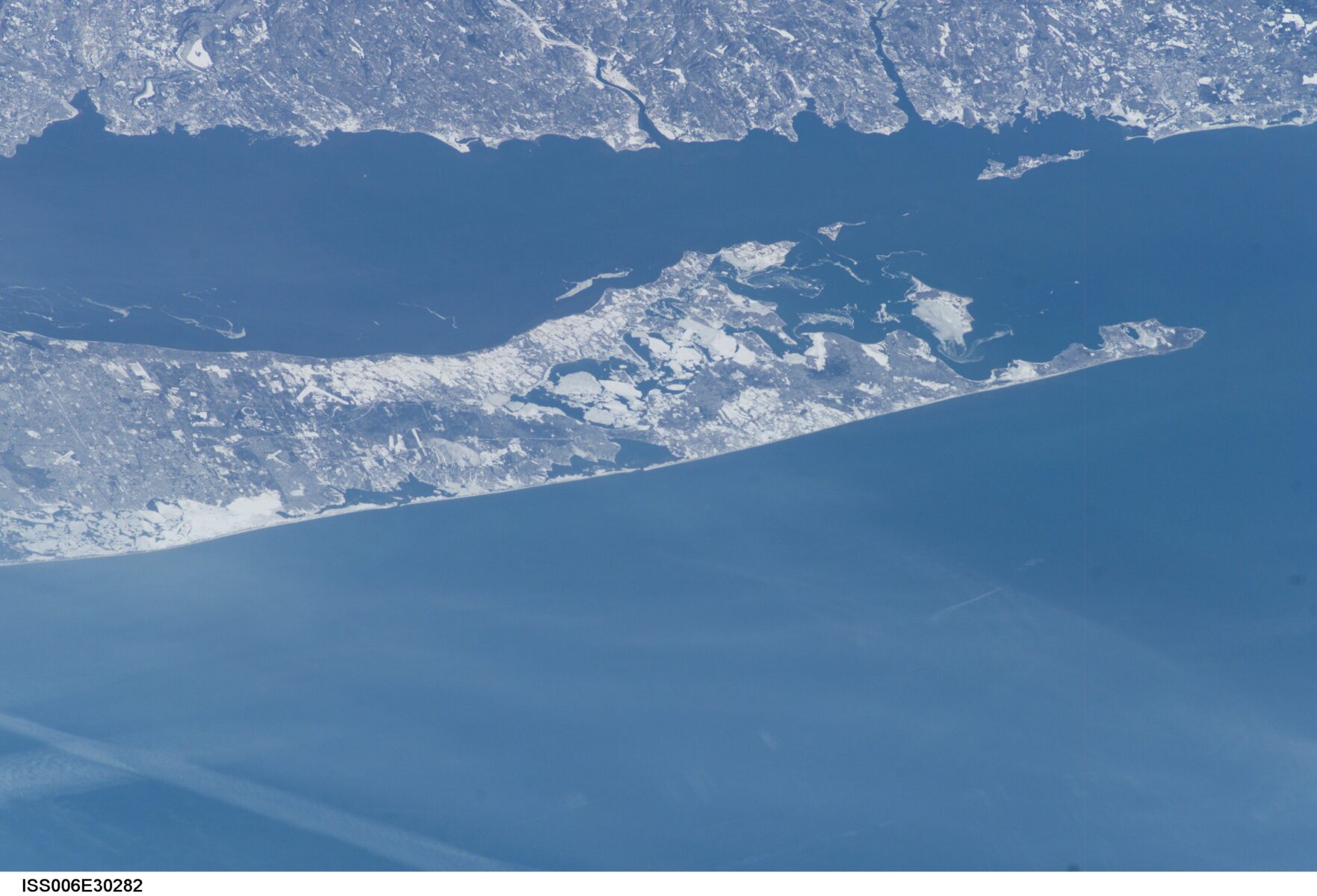

LIPBS 2023 Wrap Up

Last year we held a yearly wrap up on our social media accounts. It was an enjoyable way for us to recount the year’s events in an episodic way, highlighting a different event each week leading up to the New Year. This year we wanted to do something similar, but here on the LIPBS website instead! This way, you can binge through all our highlights from this year at once, instead of needing to wait a week to get your fix of the LIPBS!

Let’s open this with our big event from the summer, the 30th Anniversary Celebration of the Pine Barrens Protection Act! Or rather, the 30th Anniversary Celebration of the *Signing* of the Pine Barrens Protection Act. Our event was held in the very same Southaven County Park where former Governor Mario Cuomo signed the act into law in 1993. There, the founders of the LIPBS were joined by current staff, as well as supporters and locally elected representatives, all to celebrate the anniversary of the landmark act.

Credit: Wayne Cook

At the event we reminisced about the past, but also looked to the future with our “The Best of The Rest initiative,” which has currently brought approximately 900 acres out of the desired 3,800 to the appraisal/negotiations/acquisition table. Playing between speakers, was the very same band that played at the original signing in 1993, a but older, just like the rest of us. The entire event capped off with a guided hike around the park from Society Board Member, co-founder and renowned environmentalist John Turner.

Credit: Dylan Eiden

Also at this event was the awards ceremony for our Middle School Kids Go To College program, which was held a month prior. For the first time since 2019, the college component was live, held at Stony Brook University, on the SOMAS campus. There, students from three Patchogue-Medford middle schools were treated to a lecture from Dr. Chris Gobler, a world-renowned scientist, and professor at the university. Dr. Gobler went over the water-related issues plaguing Long Island, as well as some of the solutions which have been put to work over the last few years.

Credit: Dylan Eiden

Once Dr. Gobler finished his presentation, it was time for the students to put on presentations of their own, showing off their own projects, which they had been researching and preparing for months before. These projects differed from student to student, as observed by both Dr. Gobler and the LIPBS staff. After the event had concluded, the Society staff took their time reviewing the projects, before selecting just a select few to be presented with awards at our summer celebration.

And speaking of celebrations, we once again hosted our yearly Gala in October, this time marking the 46th anniversary of the Society. This event was focused largely on recapping the two events we just went over, but did come attached with our ever popular Silent Auction, with a host of getaways and restaurant trips included as the incentives.

Regardless of what big events we hosted this year though, our focus has remained on securing parcels through “The Best of The Rest.“ Progress has been steady since we began, and we are on good pace to ensure that Long Island’s open space will stay preserved for generations to come.

By Andrew Wong, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Posted on December 19, 2023 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Sharing the Road

As anyone who’s ever had to take a back road on the north shore can tell you, Long Island has an abundance of wild turkeys. Around now they can be a bit of a festive sight to see crossing the road, but any other time of the year it can be a bit stressful to see these big birds loitering in the middle of the road. You really don’t want to hit one of these birds while they’re just hanging out so you might find yourself just sitting and staring at them for a few seconds, waiting for them to cross the road. This isn’t an experience unique to turkeys though, as plenty of us have probably had one or two scares when a deer jumped in front of us out of some brush.

Credit: Brookhaven National Lab

In general, avoiding these big birds can be a challenge, especially because of how well their dark feathers blend into the color of the ground and trees. This, combined with just how calm turkeys tend to be around humans, makes them a real risk on the road. So, be sure to practice basic driving safety, eyes on the road and all, but even then there’s a real chance you might not see a group of turkeys until you’re just a few yards away from them. In these sorts of cases, assuming you’re going the speed limit, combined with how low that limit is on most back roads where you’re likely to encounter a turkey, a sudden stop should still be perfectly safe.

Of course, if you’re going well over the limit, or maybe on a road where the limit is much higher, a sudden stop can be dangerous. Tempting as it might be to swerve out of the way of a pack of birds, the sad reality is that a turkey is a whole heck of a lot softer than the trunk of a tree, and if there’s not ample road, you’re a lot better off not risking a hospital trip over a couple of them. This is of course, a last resort scenario. Ideally you’ll either be going the speed limit, or have enough road that a higher speed swerve won’t take you off the road. In any other situation though, it’s important to place the safety of yourself and your passengers first.

A beautiful bird, but not worth your life.

All of this is magnified in hazardous weather conditions. If there’s heavy fog or worse, heavy rain, then the odds of you being able to see anything in front of you, much less something rushing out of the brush, is low. If an unfortunate turkey or deer jumps out in front of you trying to make any evasive maneuver, even going a reasonable speed, will put you and other drivers at risk. If you do happen to hit something in hazardous weather, it’s important not to stop driving, or to look behind you to assess damage done. If you want to check on the wildlife you collided with, gradually slow down, and pull over some distance ahead. Stopping suddenly or taking your eyes off the road puts everyone in danger, and you should only go to investigate once you’re safely parked on the side of the road.

We realize this isn’t a particularly enjoyable conversation to have at any time of year, but with winter coming soon and recent bouts of heavy fog, it’s important to take all possible measures to keep yourself and others safe on the road. We all love our wild neighbors on the island, but if the worst-case scenario happens, it’s important to place you, your passengers, and other drivers’ safety above that of the wildlife. An animal collision is tragic, but not as much so as a car driven into a tree or home.

By Andrew Wong, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Cover Photo by Matt Foster on Unsplash

Posted on November 28, 2023 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Splash: Clean Water Now Recollection

Last week, we hosted our 46th Annual Environmental Gala! There was quite a leadup to the event itself, and after a live broadcast on Facebook and a Premiere on YouTube, everyone at the Society got to breathe a sigh of relief. In case you missed the Gala, you can watch the full video now on YouTube! But, in case you were looking for something more newspaper adjacent to go with your morning Coffee, we’ll also be summarizing it here!

A Lot of the footage for this year’s Gala actually came directly from our Summer celebration of the 30th Anniversary of the Pine Barrens Protection Act’s signing! We covered that whole event in a separate blog post back over the summer, but we’ll run it down quickly here. Opening speeches from Executive Director Dick Amper and Society Board Member Tom Casey opened the event, with kind remembrance of the work done and some light humor. After they got their words in, a number of local politicians took the stage to recount their own experiences with the Pine Barrens Protection act, and where they were when the Act was passed. This section of the Gala was closed out with some music from the Sunnyland Jazz Band, the same band that played all those years ago when the act was first signed!

John Turner, John Cryan, Ed Romaine, and Dick Amper

The next section of the Gala was a recounting of our yearly Middle School Kids Go To College program, with a brand new video produced just for the Gala! In it, We showed off some of the event itself, from our grand assembly of 3 different schools at Stony Brook University, to our individual visits to each school, you’ll get to see every bit of the program right from the comfort of your home! Once we were done at the schools, we went back to our 30th anniversary celebration to present individual awards to some of the winning students!

Dr. Christopher Gobler and Dick Amper

Finally, the event closed out with an important presentation by Society Board Member and environmentalist John Turner on our new initiative, The Best of The Rest. In his presentation John covered all the different parcels we’re still fighting to preserve, as well as the various flora and fauna which inhabit the parcels. Not naming this year’s gala after the initiative doesn’t mean we’re pushing The Best of The Rest any less, and we’re always working behind the scenes with local government and other non-profits to try and secure as much of the land for preservation as possible.

John Turner speaking about The Best of The Rest

And with that, our Gala was closed out by Executive Director Dick Amper, before shifting into some highlights of our special Silent Auction (which may or may not be over by the time you read this). The Gala season is, to put it lightly, a bit of a busy time for us, but every bit of the work we do is worth it to share with people our continual progress and history.

We hope you enjoyed watching Splash: Clean Water Now as much as we enjoyed putting it on. We’ll see you next year for our 47th Gala!

By Andrew Wong, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Posted on October 30, 2023 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society