I was forced to retire early in mid-2015. My wife, Christina, had had open-chest surgery the year before, and though she made it through that, she was never the same afterwards. I moved upstate full-time to care for her in the cabin we’d built together over the previous decades, up in what we called ‘The Land of Manitou’, otherwise known as the Catskill High Peaks. She wanted to stay there.

During the years that followed, Christina’s condition declined further. She developed several serious autoimmune disorders which compounded her pain and suffering. I did the best I could in a very remote location, and luckily had a sympathetic and competent general practitioner and pharmacist within a few miles willing to make house calls when necessary. For her last five years, Christina was bedbound on oxygen 24/7.

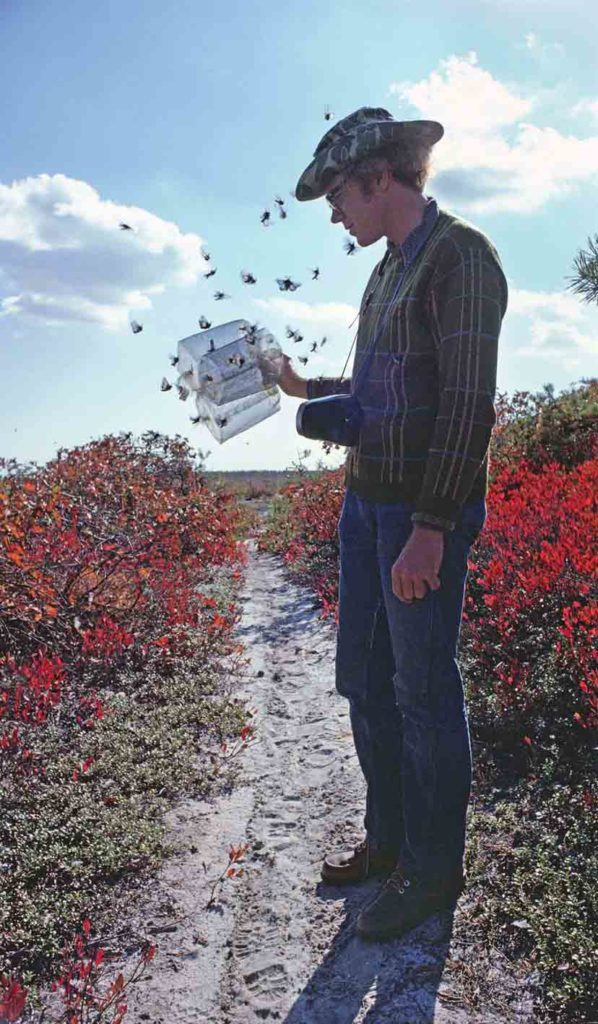

Before that happened, in the evenings I spent small amounts of time starting to organize the results of a project I had begun in my teen years, which morphed after college into a lifetime pursuit, a single, 50-year-long ‘life experiment’ – crossing various populations of Buck Moths from across the US in an attempt to figure out who was related to whom, and what unknown force had created a new kind of Buck Moth my best college friend Bob Dirig and I had discovered in 1977, my senior year at Cornell.

By the end of 2016 I hadn’t progressed far. Christina had gotten worse and worse. I managed with her permission to sneak off to the tiny local library for a half hour every now and then in a desperate attempt to speed-read online science papers from the last half-century hoping to find some sort of clue.

That effort came up empty, though I caught up with a lot of science.

A tiny bookstore opened in the local village. With no internet at home, that became my last resort.

I couldn’t afford to be away from Christina, but I could afford to buy books, especially paperbacks.

Chaos became my mantra and my business. I made a study of it.

What I found out was nobody knew much about it. There was a new thing in science called ‘Chaos Theory’, but it wasn’t really about chaos. It was about randomness, a totally different thing, and it included some kind of new bullshit called ‘Complexity Theory’, or, if you will, ‘Emergent Complexity.’

There were popular bestsellers over the past few decades about this malarkey. But on actual chaos? Nothing. Neither scientific nor popular writing. A huge void. An empty space big as the Universe.

“Why was that,” I asked myself. Something’s seriously amiss here. Scientists are usually not afraid to study anything. What makes chaos such a no-no?

What I found in pretty short order was that scientists weren’t avoiding chaos; they had no ability to study it. That’s because chaos is not amenable to math. Math can’t model it. And since math is the language of scientists, scientists just ignored chaos. They studied order only, because that’s what math can do – model order. Not chaos. Randomness was the closest to chaos math could come. But randomness is a form of order. It has rules. Chaos doesn’t. That’s why it’s called chaos.

So, I was stuck. As the country went haywire, I contemplated chaos and what it meant to have such a huge gap in science. After all, chaos is everywhere. The newspapers I brought to Christina to read in bed every day were full of chaos.

Somewhere in 2017, I had an epiphany. The epiphany turned into a brainstorm. I started scribbling.

The epiphany centered around something in one of Darwin’s notebooks, which had been lost awhile but recently found again. It was a simple question: ‘Why is life short’. Darwin had scribbled it so fast he forgot the question mark at the end. But a question it was anyway, and a really big one at that.

When I read about the lost and found notebook containing the really big (big because neither Darwin nor anyone else had ever found a satisfactory answer to it) question, I realized this was the key to my dilemma. Solve that question, and I will solve the Buck Moth mystery, and probably much more.

And chaos certainly lay at the center of any solution. It was the biggest thing I knew that science couldn’t touch.

So I took one last quick trip to the library to get a list of the biggest gaps in science. The unanswered questions scientists were dying to answer, but didn’t know how or have the tools yet to study. At the heart of just about all of them lay more than a bit of chaos.

I also found out about interlibrary loans. This tiny branch had access to the entire Hudson Valley. Now I was in business.

I made a map of all the gaps in science, and determined to fill them, realizing chaos was what was missing. And I bought, and took out, a ton of books. Each night, I read whenever I couldn’t sleep.

One by one, the brainstorms came over the next three years, like a pinball game lighting up. Bing-bang-boom! Before I knew it, one thing had led to the next to the next and I had two interlinked, brand-new scientific theories, one in physics, the other in biology, specifically evolution. Chaos lay at the heart of all of it. The Chaon-Convolution Theory was born.

I kept my friend Bob, who is a polymath in the arts and sciences, totally in the loop. He got all my ravings, all my scribblings. All he said was “when you’re done, send it all to me and I’ll turn it into a science zine. This is your life thesis.” Thus was born Moths of the Past.

It was published by our longtime mutual friend Don Rittner, who himself has authored and edited over 30 books. It came out three years ago, just as the pandemic hit full force. Don had to coax the hard copies out of the last printhouse still running in America, down in South Carolina. But out it went, into a world in agony. We sent out several hundred author copies to select people and institutions around

the country and world. Because of its enormous scope, and Bob’s creation of a work that truly blended art and science, we deliberately went for as wide an audience as possible, knowing scientists would probably be the last to embrace it, or even deal with it at all. After a year, we went to free internet distribution, and Moths of the Past went viral. It has been read by millions, around the world, and its audience is constantly expanding.

Somehow, over the last few years, I was able, again working in bits in the middle of the night, to complete and distribute 14 additional implications white papers, supplements to the original concepts in Moths of the Past, both expanding and extending them. I’m working on more now.

But in that same period, my beloved Christina slowly weakened. She never lost her mind, her love or her fighting spirit. On the early morning of February 16th, at sunrise, she left this world. I miss her.

By John Cryan, Long Island Pine Barrens Society Founder

Cover Photo by Don Henise

John Cryan with Buck Moths