Who Knows Where the Time Goes?

“The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: What good is it?”

–Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

November 25th, 1983 marked the beginning of a new era for Long Island, its rare and threatened wildlife, and perhaps most importantly, for the people who call it home. On that date, I, along with my two closest friends, John Cryan and John Turner (the “bushwhackers” to our friends), took documents we had painstakingly typed on a Smith-Corona typewriter to a local drugstore in Commack. We needed the Certificate of Incorporation for the Long Island Pine Barrens Society to be notarized. Notary Public Jo-Ann Davino signed the document and affixed her notary stamp. The Society was now official; it would go on to become the most influential and effective environmental organization on Long Island.

Prior to this we had spent many years “bushwhacking” around the Pine Barrens. Long days in the field collecting Buck Moth caterpillars and looking for those ever-illusive carnivorous plants, rare ferns, and orchids that Long Island naturalist Roy Latham first discovered some 60 years earlier. Alas, that was some 45 years ago!

Where has the time gone? Yes, it was a time when the only things we worried about were having enough rolls of Kodachrome 25 for our cameras, and enough money for gas. I often reflect on that time in our lives as a period when I learned a true respect for the natural world in which we live. It was a time when we learned the value of the natural ecosystem that surrounds us and why people so desperately needed to understand that humanity is as much a part of it as the Buck Moth, Northern Pitcher Plant and Dragon’s Mouth Orchid.

The Society and its three “bushwhacker” executive directors realized many singular victories, beginning with helping to preserve the Radio Corporation of America’s holdings in Rocky Point and Riverhead in 1978. Next was the curtailing of illegal golf courses in Calverton (we were too late to halt the construction of one illegal course, which now serves as a primary point source of nitrogen pollution to the Peconic River watershed!). Next came the successful relocation of a proposed free trade zone in the southeast quadrant of the Dwarf Pine Plains, but not before the developers illegally bulldozed forty acres when they recognized that there was dwindling support for their project at this location. These successes were instrumental in laying the groundwork for the Society’s crowning achievement: the Pine Barrens Preservation Initiative, which began in 1989.

During the first dozen years, we fought tirelessly for the preservation of key properties. The Oakbrush Plains at Edgewood, the Bishop tract, Maple Swamp, and Hampton Hills, all priority acquisitions at the time. I often think of those victories with shear astonishment. Three young “bushwhackers,” John Turner as President, John Cryan as Vice President, and me as Secretary and Treasurer. Heck our address was John Turner’s post office box in Smithtown! Truth be told I was just out of high school and seventeen when we had our first thousand sheets of stationery printed by my future father-in-law for a whopping $13.00! It was quite humorous when nobody seemed to be able to figure out which way our logo (a Buck Moth) was flying, or what it was, for that matter. And yet, we as the officers of the Society, have never lost sight of our goal.

Yes, those truly were the days!! Long days in the field when we loaded up John Turner’s Volkswagen Beetle with bug nets, our cameras and plant presses and stayed out “in the field” from dusk till dawn. Back then, nobody paid attention to us. After all, how can you take someone seriously when they bring a buck moth with them when testifying at a congressional hearing in Southampton? Yes, we absolutely were different, but I am proud to say that the three of us are still here. You can’t say the same for self-proclaimed Pine Barrens political preservationists like Steve Levy, Bob Gaffney, Peter Cohalan and Steve Bellone.

It was these hard-fought battles that led us to change environmental policy in New York State. The date was November 21, 1989, when our little-known environmental organization, one with grit, conviction, integrity, and soul brought the largest lawsuit of its kind in the nation against local government in an effort to safeguard our environment and its natural resources from future degradation.

To say we caught the media, local government, and the development community completely off guard was an understatement. “Who are these people?”, I overheard many reporters asking as they milled about waiting for the press conference to begin at the Middle Island Country Club. “After all no environmental group could possibly be this well organized,” they could be heard mumbling amongst themselves. We had a three-dimensional map identifying the priority properties of critical concern, a podium emblazoned with our logo (which we had now changed from a buck moth to an outline of Long Island with the Pine Barrens strategically placed), and yes, we even served Danish and coffee. So befuddled were the media covering the event that the first question one of them asked was, “Who paid for all this?” A Pulitzer award winning reporter if ever there was one, I thought to myself!

That eventful day led to a ruling handed down by the Appellate Court in March 1992 that required cumulative impact studies if development threatened the integrity of the Pine Barrens. These studies were to be conducted before any further development took place. While the ruling was overturned by the following November, it set in motion a series of events which culminated with the now famous “Why Can’t Long Island” campaign” on April 12, 1992.

This led to a “meeting of the minds” at the Long Island Association in Commack on April 25th where, as President of the Society, I first introduced our dog-eared map to the masses of politicians, businessmen and developers. This was the map we had used for every political meeting, slide show, hike, or hearing we had ever attended. This map, which we so painstakingly colored in with colored pencils was our “vision,” if you will, of what a Pine Barrens Preserve should look like.

Personally, I thought the meeting was a pathetic demonstration of arrogance on the part of the invited politicians and the developers. Even some allegedly “environmentally minded” people were playing politics. Still, after over three hours, they agreed that something needed to be done to end the “war of the woods,” as our campaign had been called by the press. Within ten weeks we secured a path to preservation – our dream was realized. Today, we can look back and be grateful.

Reflections such these are what I turn to when anyone, be it a developer or fellow environmentalist, asks me, “what is the Long Island Pine Barrens Society?” I guess, plainly and simply, we are nothing more than a group of devoted individuals who care about Long Island’s future. Given all the politics, personalities, economics, and egos that have come into play where the Pine Barrens is concerned, it impresses me that the Society has survived since the 1970’s. And yet somehow it has, and we are on the verge, with our newly introduced “The Best of the Rest” campaign, of making certain that adequate amounts of this fragile and wondrous landscape remain forever wild for future generations to enjoy and discover.

So, to bring this piece full circle, I titled it “Who Knows Where the Time Goes?” Anyone who has ever read one of my articles knows I always include a musical quote. The title of this one comes from songwriter Sandy Denny and made famous by American folk singer Judy Collins.

Across the evening sky

All the birds are leaving

But how can they know

It’s time for them to go?

Before the winter fire

I will still be dreaming

I have no thought of time

For who knows where the time goes?

By Bob McGrath, Long Island Pine Barrens Society Founder

Misty Watercolor Memories

It is very difficult to select memories to reminisce about after 45 years with the Long Island Pine Barrens Society, all to secure the permanent protection of the Long Island Pine Barrens. Literally hundreds of memories from hikes and field trips, speaking engagements (scores of slide lectures about the Pine Barrens to diverse audiences), public hearings, court testimony, lobbying activities in the halls of Hauppauge and Albany, and, of course, quarterly board meetings of the Society at which we strategized to set policy and direction.

The Following are but a few.

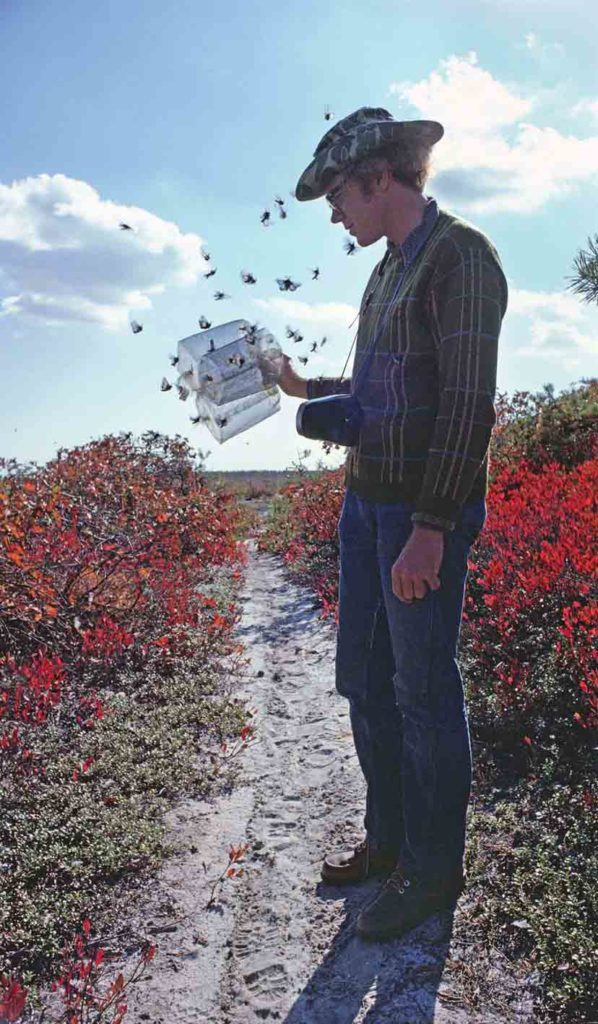

I remember well several hikes, a few of which were in the Dwarf Pine Plains. Early in the Society’s existence we led many hikes to promote public awareness of the Pine Barrens. One of the more successful hikes involved co-founder John Cryan leading a walk to see buck moths during their annual autumn mating flight. Prior to the start of the hike John found several female buck moths. He put them in a fine wire cage where, hanging from the top, they began to do what female buck moths do: release pheromones to lure males to create the next generation of moths. And lure they did for quickly a dozen or so males, adorned in their beautiful white, black, and orange coloration converged on the cage trying to get inside to mate! The more than 50 participants were excited to see up close one of the iconic species of the Pine Barrens.

The Dwarf Pine Plains have been the site of several other memorable encounters. Leading a hike of a dozen people on a full moon night to listen for “goatsuckers”, such as whip-poor-wills and chuck-will’s-widows about a decade ago, we walked through the Dwarf Pine Plains listening for their distinctive calls. By the end of the hike, we had heard a dozen “whips” and three “chucks.” I’ve two special memories from hiking the Plains in which I came across two rare Long Island mammals – striped skunk and grey fox. Both were foraging for food and because they were so focused on their search, I was able to get a wonderful close up view of each species.

Another hike that I led with co-founder Bob McGrath took place further west in a large expanse of Pine Barrens, Manorville Hills, the largest block of contiguous open space found on Long Island. Approximately 25 participants were treated to a stunning display of an eastern hognose snake going into its famous “death feign act” whereby the disturbed snake, coiled alongside a sandy trail, went into spasms and convulsions, turning over on its back, with its tongue hanging out of its mouth, “dies.” Another “herp” I have a special memory of was seeing a congregation or breeding congress of tiger salamanders in a pond in Manorville. Male and female salamanders were entwined in a ball in the water in a breeding frenzy; this activity results in male salamanders laying sperm packets or spermatophores on the pond bottom, which a female salamander will straddle and bring it into her body.

A “threatening” Hognose Snake. Photo by Bob McGrath

Another memory I have with Bob is when we traveled to the World Trade Towers to participate in an Army Corps of Engineers. The hearing was focused on the filling of freshwater wetlands just south of Swan Pond to construct a golf course. We made the mistake, being young, enthusiastic and foolish, of running up 45 flights of stairs. We were winded quickly and the hearing didn’t go much better as the Corps, mind-bogglingly, issued the permit to allow for the destruction of the wetlands. To this day, the golf course remains an ecological travesty – a use of the land that destroyed wetlands and forest, and which continually inputs fertilizer into a naturally nutrient poor ecosystem.

The Society has conducted a fair amount of lobbying in advancing the protection of the Pine Barrens and two events stand out. Mike Deering, who was Society president for a while, and I were at the Suffolk County Legislature in Hauppauge to express support for an amendment to the Suffolk County Drinking Water Protection Program; at that time the land acquisitions were “pay-as-you-go”, meaning the funding used for land purchases was made available on an annual basis. Since land values were escalating rapidly, we argued the County should bond for the money as this would result in more properties ultimately preserved, even though the County’s overall amount of money would be reduced because of necessary interest payments on the bonds. We pigeonholed then county legislator Steve Levy, a very fiscally conservative lawmaker, in the hallway next to the auditorium speaking to argue our point that although the County would be required to pay interest, more acreage would be preserved – the very purpose of the land acquisition program. While Levy still voted against it, the measure, thankfully, was amended and the County bought lots of Pine Barrens properties.

Yet another significant memory was the first time I communicated with Dick Amper, the long-serving Executive Director of the Society. It was through a phone call on a Sunday night. Dick called to learn more about the Pine Barrens as he and other neighbors were fighting to stop a development from being constructed on the eastern side of Lake Panamoka. I could tell he was quite interested and intense and a very quick learner. One thing led to another, and the development was stopped, the property preserved, and the Board of the Society realized that Dick was a very talented person. — a many decade long relationship was born. Combining Dick’s public relations and media acumen with the other talents of Society board members proved to be an unbeatable combination!

Perhaps the memory that is foremost in my mind occurred on a spring night in Albany in 1993. After many months of negotiating between the LI Pine Barrens Society and the towns and developers, the Long Island Pine Barrens Protection Act was passed by the New York State Legislature. The same night the state legislation creating the Environmental Protection Fund passed, providing funding to purchase lands in the Core Preservation Area of the Pine Barrens. It was a great night and fun to be sitting in the gallery of the NY State Assembly when the final vote was tallied. A close second was the press event at Southaven County Park, several weeks later, at which Governor Mario Cuomo signed the measure into law.

These memories depict “The Way We Were.” With the Society’s advancement of the “Best of the Rest” Initiative, I’m hoping we’ll develop many more pleasant watercolor memories to add to the collection.

By John Turner, Long Island Pine Barrens Society Founder

Cover Photo by John Cryan

The Genesis and Meaning of Moths of the Past

I was forced to retire early in mid-2015. My wife, Christina, had had open-chest surgery the year before, and though she made it through that, she was never the same afterwards. I moved upstate full-time to care for her in the cabin we’d built together over the previous decades, up in what we called ‘The Land of Manitou’, otherwise known as the Catskill High Peaks. She wanted to stay there.

During the years that followed, Christina’s condition declined further. She developed several serious autoimmune disorders which compounded her pain and suffering. I did the best I could in a very remote location, and luckily had a sympathetic and competent general practitioner and pharmacist within a few miles willing to make house calls when necessary. For her last five years, Christina was bedbound on oxygen 24/7.

Before that happened, in the evenings I spent small amounts of time starting to organize the results of a project I had begun in my teen years, which morphed after college into a lifetime pursuit, a single, 50-year-long ‘life experiment’ – crossing various populations of Buck Moths from across the US in an attempt to figure out who was related to whom, and what unknown force had created a new kind of Buck Moth my best college friend Bob Dirig and I had discovered in 1977, my senior year at Cornell.

By the end of 2016 I hadn’t progressed far. Christina had gotten worse and worse. I managed with her permission to sneak off to the tiny local library for a half hour every now and then in a desperate attempt to speed-read online science papers from the last half-century hoping to find some sort of clue.

That effort came up empty, though I caught up with a lot of science.

A tiny bookstore opened in the local village. With no internet at home, that became my last resort.

I couldn’t afford to be away from Christina, but I could afford to buy books, especially paperbacks.

Chaos became my mantra and my business. I made a study of it.

What I found out was nobody knew much about it. There was a new thing in science called ‘Chaos Theory’, but it wasn’t really about chaos. It was about randomness, a totally different thing, and it included some kind of new bullshit called ‘Complexity Theory’, or, if you will, ‘Emergent Complexity.’

There were popular bestsellers over the past few decades about this malarkey. But on actual chaos? Nothing. Neither scientific nor popular writing. A huge void. An empty space big as the Universe.

“Why was that,” I asked myself. Something’s seriously amiss here. Scientists are usually not afraid to study anything. What makes chaos such a no-no?

What I found in pretty short order was that scientists weren’t avoiding chaos; they had no ability to study it. That’s because chaos is not amenable to math. Math can’t model it. And since math is the language of scientists, scientists just ignored chaos. They studied order only, because that’s what math can do – model order. Not chaos. Randomness was the closest to chaos math could come. But randomness is a form of order. It has rules. Chaos doesn’t. That’s why it’s called chaos.

So, I was stuck. As the country went haywire, I contemplated chaos and what it meant to have such a huge gap in science. After all, chaos is everywhere. The newspapers I brought to Christina to read in bed every day were full of chaos.

Somewhere in 2017, I had an epiphany. The epiphany turned into a brainstorm. I started scribbling.

The epiphany centered around something in one of Darwin’s notebooks, which had been lost awhile but recently found again. It was a simple question: ‘Why is life short’. Darwin had scribbled it so fast he forgot the question mark at the end. But a question it was anyway, and a really big one at that.

When I read about the lost and found notebook containing the really big (big because neither Darwin nor anyone else had ever found a satisfactory answer to it) question, I realized this was the key to my dilemma. Solve that question, and I will solve the Buck Moth mystery, and probably much more.

And chaos certainly lay at the center of any solution. It was the biggest thing I knew that science couldn’t touch.

So I took one last quick trip to the library to get a list of the biggest gaps in science. The unanswered questions scientists were dying to answer, but didn’t know how or have the tools yet to study. At the heart of just about all of them lay more than a bit of chaos.

I also found out about interlibrary loans. This tiny branch had access to the entire Hudson Valley. Now I was in business.

I made a map of all the gaps in science, and determined to fill them, realizing chaos was what was missing. And I bought, and took out, a ton of books. Each night, I read whenever I couldn’t sleep.

One by one, the brainstorms came over the next three years, like a pinball game lighting up. Bing-bang-boom! Before I knew it, one thing had led to the next to the next and I had two interlinked, brand-new scientific theories, one in physics, the other in biology, specifically evolution. Chaos lay at the heart of all of it. The Chaon-Convolution Theory was born.

I kept my friend Bob, who is a polymath in the arts and sciences, totally in the loop. He got all my ravings, all my scribblings. All he said was “when you’re done, send it all to me and I’ll turn it into a science zine. This is your life thesis.” Thus was born Moths of the Past.

It was published by our longtime mutual friend Don Rittner, who himself has authored and edited over 30 books. It came out three years ago, just as the pandemic hit full force. Don had to coax the hard copies out of the last printhouse still running in America, down in South Carolina. But out it went, into a world in agony. We sent out several hundred author copies to select people and institutions around

the country and world. Because of its enormous scope, and Bob’s creation of a work that truly blended art and science, we deliberately went for as wide an audience as possible, knowing scientists would probably be the last to embrace it, or even deal with it at all. After a year, we went to free internet distribution, and Moths of the Past went viral. It has been read by millions, around the world, and its audience is constantly expanding.

Somehow, over the last few years, I was able, again working in bits in the middle of the night, to complete and distribute 14 additional implications white papers, supplements to the original concepts in Moths of the Past, both expanding and extending them. I’m working on more now.

But in that same period, my beloved Christina slowly weakened. She never lost her mind, her love or her fighting spirit. On the early morning of February 16th, at sunrise, she left this world. I miss her.

By John Cryan, Long Island Pine Barrens Society Founder

Cover Photo by Don Henise

John Cryan with Buck Moths