History of “The Hills”

If you’ve been following us for a while, then you know that we’ve been fighting a massive development project proposed for the East Quogue Pine Barrens, for quite some time!

It’s been a long and sometimes confusing process for everyone involved. The project has moved through several layers of government. There have been victories and losses. As we approach one of the most important hearings for this project later this month (more on that later), we thought we would provide proper background coverage on where we are today and how we got here.

The Beginning

In 2013, an application for “The Hills at Southampton” was submitted to the Town of Southampton, requesting a zoning-change under the Town’s Planned Development District (PDD) code. Although this started the process we’re in now, discussions and fights against this project date back to at least 2007.

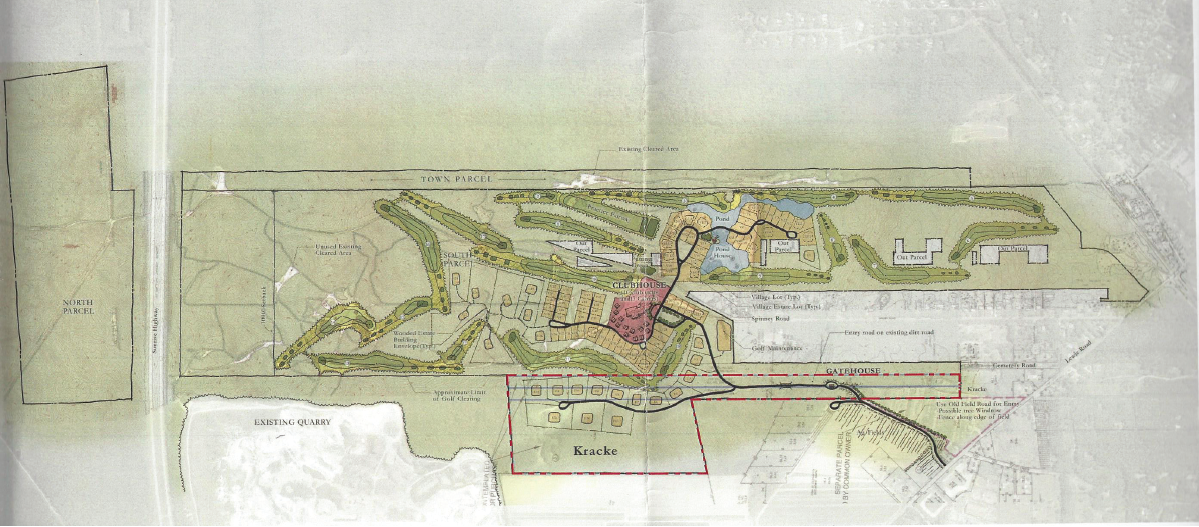

What’s Proposed

The developer, Arizona-based Discovery Land Company, proposed to build 118 mansions, a 98 acre private golf course, a 155,000 square foot club house, and several other amenities and structures, on 590 acres of pristine Pine Barrens in East Quogue. The development site is also located in a state-designated Special Groundwater Protection Area, as well as a Suffolk County-designated Critical Environmental Area. In addition, the site is also part of a group of lands which The Nature Conservancy has given top priority for permanent preservation.

The development site, located in the East Quogue Pine Barrens.

The PDD Process

From 2013 to 2017, the Pine Barrens Society and many other environmental and civic groups, banded together to participate in the Planned Development District (PDD) and the State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA) processes. While we worked to pull the community together – holding community forums, bringing in scientific experts, canvassing the neighborhood – the developer took a different approach. They hired people in the town to advocate on their behalf, they promised people jobs, they promised multi-million dollar “community benefit projects,” they set up food trucks outside public hearings, and they donated tens of thousands of dollars to political campaigns.

We reviewed hundreds of pages of documents and participated in countless hearings for these four years. Our coalition even worked to produce an environmentally-safe alternative for the site, if preservation options were truly off the table. We wrote letters to the editor, held rallies and lobbied local elected officials.

Rally Against “The Hills”

In the end, our hard work paid off. In December of 2017, the Southampton Town Board voted down the project. The town also repealed the PDD legislation. We were thrilled about the result, but knew the developer still owned the land and that our work wasn’t over yet.

The Lawsuit

The developer, who spent years touting what “good neighbors” they are, and how much they cared about the people of the town, immediately filed a $100-million lawsuit against the town and the two town board members who had the courage to vote against the project. This suit is still pending.

The Village

Once the project was voted down by the Town Board, proponents of the project, launched an effort to incorporate the village of East Quogue. Several members of the Village Exploratory Committee, witnesses of the signatures on the petition, the notary of the petition, and many of those who signed the petition for incorporation, had vested interests in Discovery Land Company and had been vocal advocates of the Hills project. One member of the exploratory committee was a paid consultant of Discovery. They had hoped that they would take the decision power out of the hands of the town and be able to re-run their project under a newly-formed village government. While this effort was a local town issue, we knew we had to get involved, because we knew that this was just another attempt to get “The Hills” approved.

After a few more months of work within the community, and advocacy, the residents of East Quogue voted down the idea of incorporating East Quogue into a village. The project would remain in the hands of the Town of Southampton.

The Lewis Road PRD – Same Project, New Name

Just months after the Town Board voted down the “Hills at Southampton,” the developer filed a nearly identical project under a different piece of zoning code, called a Planned Residential Development (PRD). The new project was named “The Lewis Road PRD.” Ironically enough, the developer filed for the project under the town’s Open Space Law. The project would now be reviewed by the Southampton Town Planning Board. The developer argued that its professional golf course was simply a recreational amenity to their now 130 home development project. However, the golf course wasn’t the only proposed amenity – they also proposed a baseball field, a practice fairway, a fitness center, pool, basketball court and four pickle ball courts.

The Planning Board, was not sure if a professional golf course could be considered a recreational amenity, as outlined by the Town’s Open Space Law and PRD ordinance. This had never been done before, and a golf course was not listed as an approved amenity in the town code. Therefore, they asked the Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) for clarification.

The Society and our coalition testified at these hearings before the ZBA. We argued two things:

(1) The Open Space Law and the PRD ordinance explicitly do not allow for golf courses as a recreational amenity to a development project. Several leading planners testified the same, including Assemblyman Fred Thiele, who wrote the town’s Open Space Law many years ago.

And

(2) If the project would have been allowed to pass through under the Planned Residential Development zoning from the beginning, wouldn’t the developer have proceeded with this route in the first place, instead of trying to get their project approved under the more difficult Planned Development District zoning? In fact, the developer had stated years prior in legal documents that the PDD process was that they could proceed with their project. However, here they are now, arguing the opposite.

The Southampton Town Zoning Board of Appeals sided with the developer, and stated that the golf course could be considered a recreational amenity. After this, the Group for the East End filed a lawsuit challenging this decision; we joined them along with Assemblyman Fred Thiele, the East Quogue Civic Association and several neighbors that abut the property.

The project then bounced back to the Town Planning Board. Our coalition showed up again, testifying before the Board. We made all of our original arguments, along with new arguments about how the Town had completely botched the State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA) process in its review of this new project. Nevertheless, the Town Board approved the preliminary application. Group for the East End sued again, and we joined them again too.

Luckily, our lawsuits have placed a temporary restraining order over the site until they are settled. The developer cannot break ground until the lawsuits are settled.

The New York State Pine Barrens Commission

Since the Southampton Planning Board approved the preliminary application, the project finally heads to the New York State Pine Barrens Commission for review. We have reviewed the 174 page application sent to the Commission, and have determined that the Lewis Road PRD does not comply with at least 28 guidelines of the Comprehensive Land Use Plan. We will be submitting a report on this and participating in the hearing before the Commission, to be held on Wednesday, February 19th at 2:30 pm at Riverhead Town Hall. More details on the hearing can be found here.

We need your help! This hearing before the Pine Barrens Commission is our last chance to voice our concerns about this project. We need as many people as possible to turn out to this hearing. This project doesn’t comply with the Pine Barrens Act and the Commissioners need to hear that the public wants to see our Pine Barrens protected! We hope to see you there.

By: Katie Muether Brown, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Posted on February 6, 2020 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

What is the Long Island Pine Barrens?

What is the Long Island Pine Barrens?

Heading east on the Long Island Expressway, just after passing exit 63, you will notice fewer buildings and begin to see beautiful tracts of forested lands. It’s the Long Island Pine Barrens! Most people know it by name. Some people might even remember the fight to protect it. But, what is the Pine Barrens?

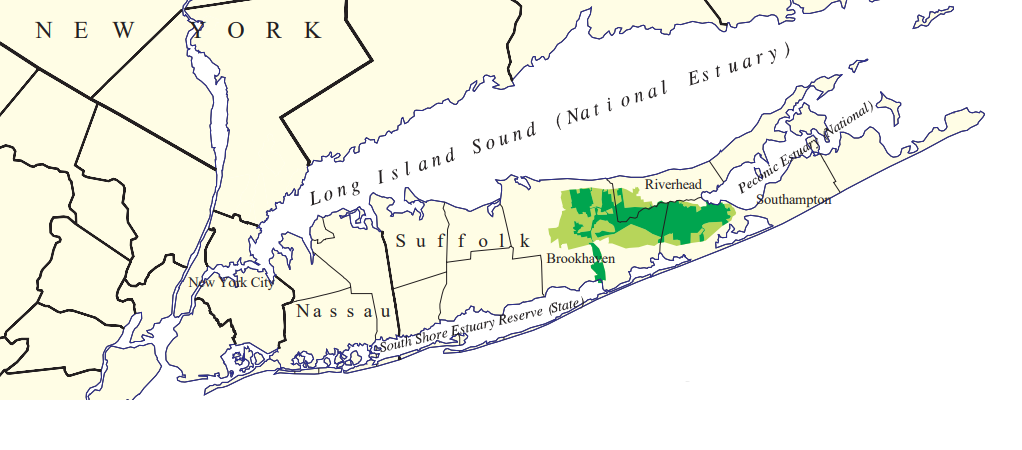

As of this year, there are 106,332 acres within the Long Island Pine Barrens, protected from development. 57,676 of those acres are placed in the “Core Preservation Area,” (dark green in the image below) where development is prohibited. 48,656 acres are in the “Compatible Growth Area,” (light green in the image below) where development is carefully monitored and allowed, but only under strict guidelines. The Pine Barrens fall within three townships – the Towns of Brookhaven, Riverhead and Southampton. We like to refer to it as “Long Island’s Central Park.”

The Central Pine Barrens – Credit: Pine Barrens Commission

But the Pine Barrens is more than just protected land. It’s a natural escape – a place you can visit, with many wonderful things to see!

The pine tree that puts the “Pine” in “Pine Barrens” is the Pitch Pine! The region is mostly dominated by Pitch Pine, but there are also Black, Scarlet and White Oaks that share the canopy in a lot of places. And in the understory, you have scrub oaks and a variety of health plants (blueberry, huckleberry, bearberry, etc.). Lichens and wildflowers can also be found along the forest floor. Over a dozen species of orchids can be found in the Barrens. There are also three types of insectivorous plants found in the Pine Barrens – pitcher plants, sundews and bladderworts.

Dragon’s Mouth Orchid

The Pine Barrens also contain a range of wetland communities – including marshes, heath bogs, red maple swamps, and rare Atlantic white cedar swamps. It also contains portions of the watershed for two major rivers – The Carmans and Peconic River – and interfaces with three estuaries of national and state importance – Long Island Sound Estuary, South Shore Estuary Reserve and the Peconic Estuary.

Cranberry Bog – Credit: Katie Brown

The Pine Barrens is also home to a globally-rare ecosystem called “The Dwarf Pine Plains,” which only exists in three areas in the world. This ecosystem is dominated by dwarf Pitch Pines that are about 3 to 6 feet in height. These trees are dwarfed because of the extremely acidic and sandy soil in the area. The sandy soils allow little available nutrients and cause water to leach out very quickly. These trees are stunted, but thrive!

Dwarf Pine Plains

The Long Island Pine Barrens is home to literally thousands of plant and animal species, many of which are endangered or threatened. Animals in the Pine Barrens include over 100 bird species, many of which are disappearing in the region, outstanding populations of butterflies and moths, including the threatened Buck Moth; and endangered or threatened vertebrates like the Eastern Tiger Salamander and Eastern Mud Turtle. In fact, the Long Island Pine Barrens boast the greatest diversity of plant and animal species in the state of New York!

Eastern Tiger Salamander – Credit: M. Mann

And for the history buffs, there are also plenty of historic sites within the Barrens! This includes the Hawkins House (built in 1850), Mary Louise Booth House (1929), Davis Town Meeting House (1750), the Longwood Estate, East Middle Island Schoolhouse (1835) and the Hard Estate Lodge (1937).

Hawkins House – Credit: Yaphank Historical Society

But perhaps the most important function of the Pine Barrens is that it overlies and protects the greatest amount of the purest drinking water in New York State. The preserved land serves as an important recharge area for our federally-designated sole source aquifer on Long Island. All of the drinking water for 2.8 million Long Islanders comes from a series of aquifers right beneath our feet. Everything we do on land has the potential to impact our water quality. Unfortunately, science conclusively shows that Long Island’s water is deteriorating in areas outside the Pine Barrens. We know that more homes, lawns, roads and businesses leads to more pollution. Without the Pine Barrens, our water quality would only be even worse off.

Long Island’s Aquifer System

The Pine Barrens is rife with recreational opportunities, including hiking, boating, fishing, biking, camping, swimming and so much more! What are you waiting for? Get out there! Check out the recreation section of our website for more information.

By: Katie Muether Brown, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Posted on January 15, 2020 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

2019 In Review

As the year comes to close, we are reflecting on all of the news and activities from the past year. We’d love to review our year with you, as many of these successes could not have been possible without the support of our members.

The Fight to Prevent the “Lewis Road PRD” (formerly “The Hills”)

The Lewis Road Planned Residential Development (PRD), proposed by Arizona-based Discovery Land Company, is an 118-unit mansion complex and massive golf resort located in the Pine Barrens, a state-designated Special Groundwater Protection Area and Critical Resource Area. The original proposal for the project was defeated by the Southampton Town Board in 2017, but the developer resubmitted the proposal under a different zoning statute and thus rebranded it as the Lewis Road PRD. The project has been railroaded through the Southampton Zoning Board of Appeals and the Planning Board. The Pine Barrens Society has joined Group for the East End in two lawsuits to block the proposed re-zoning.

While we wait to move through the courts, the project will head to the New York State Pine Barrens Commission for review. The Society does not believe the project complies with the Pine Barrens Act and its Comprehensive Land Use Plan, and that an approval by the Commission will be unlikely. We will be monitoring this review carefully and supplying testimony. We will also keep you updated on how you can join in our advocacy efforts.

Lawsuit Victory to Restore the Suffolk County Drinking Water Protection Program

Suffolk County has asked the Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court and/or the Court of Appeals to reverse a previous Appellate Court ruling that orders Suffolk to restore money taken from the Suffolk County Drinking Water Protection Program. The program, approved by a majority of voters in 1987, uses a ¼ percent in sales tax to fund important water quality improvement projects and land preservation across the county. Following a raid of the program by the County in 2011, the Society sued to protect the integrity of the program and the public’s trust.

After a six year legal battle, the Society won the case when the court agreed with environmentalists that any law created by voters at referendum can only be altered or reversed by a subsequent vote by the public. “This common sense provision of law is essential if the public is to continue funding land and water protection referenda,” said PBS Executive Director, Richard Amper. More than three billion dollars have been approved by referenda since 1978 for preservation purposes.

After winning the appeal, the Society had to return to the courts to press for a judgment that required the immediate return of the money. On December 12th, State Supreme Court Justice Joseph Farneti ordered the immediate return of $29-million to the Drinking Water Protection Program. We won!

Suffolk County Releases Long-Awaited Subwatersheds Wastewater Plan

In September of 2019, Suffolk County and its Department of Health Services released its long-awaited Subwatersheds Wastewater Plan for public comment. The comprehensive study is a blueprint for solving the island’s nitrogen crisis. It is the first science-based study to examine more than 180 watersheds across the county and establish clean water targets for each. The Pine Barrens Society has been advocating for the creation and release of this plan for several years.

Nitrogen pollution from cesspools and septic tanks seeps into groundwater and contaminates local waterways. It causes harmful algae blooms, poisons wildlife, closes beaches, and threatens the source of Long Island’s drinking water. In Suffolk County, approximately 360,000 septic systems and cesspools must be transitioned to nitrogen-reducing septic systems or connected to sewer systems in order to restore and protect drinking water, streams, harbors, and beaches.

The study makes a suite of recommendations that, if followed, will result in measurable improvements in water quality. New York State and Suffolk County have already created a program to pay for the cost of the new technology, but more funding is needed. Environmentalists are calling for a dedicated revenue stream in 2020, to support the Nitrogen removal plan.

You can learn more about the County’s water quality improvement programs here.

The Pine Barrens Society Lost an Environmental Champion

The Pine Barrens Society and Long Island lost a great environmental champion this year – Robin Hopkins Amper. She was 72 and died after a four-year battle with metastatic breast cancer. She was a charming and calming alternative to her husband’s strong-willed style and a steadying force in battles to protect Long Island’s environment in general and Pine Barrens in particular. She was a quiet, behind- the- scenes volunteer and a great people person. With her husband – they formed a team whose contributions to Long Island are immeasurable.

The Society’s Board of Directors has established an Environmental Scholarship for Long Island students focused on environmental studies and sciences, and who are committed to the environment, much the way Robin was. The Society is working independently of its other work, to create an endowment that will make grants of $3,000 for worthy and needy students who live on Long Island, regardless of where they go to school. The Robin Hopkins Amper Memorial Scholarship Fund will be an investment in Long Island’s environmental future and a memorial to an extraordinary human being.

You can read Newsday’s obituary here.

Pine Barrens Preservation Campaign Declared a Victory

The Long Island Pine Barrens Society has declared victory in its 42-year campaign to protect the source of Long Island’s purest water and the greatest diversity of plant and animals in New York State. The environmental organization will now expand its effort to improve water quality Island-wide while sharing the barrens’ treasures with Long Islanders and Long Island visitors.

The initial goal of preserving 52,000 acres of the Pine Barrens Core Preservation Area – the most sensitive part – was established with unanimous passage of the Pine Barrens Protection Act by the New York State Legislature in 1993. As of this date, 57,676 core acres have been secured using federal, state, county, town and village funds – much of it from approval by voters at referendum. Fewer than 1000 remaining acres qualify for purchase in the Pine Barrens Core. In addition, some 52,000 acres of the less-sensitive Compatible Growth Area of the barrens have been protected, surpassing the original 48,000 acre goal. The occasion was celebrated at the Society’s 42nd Anniversary Environmental Awards Gala on October 23rd at Oheka Castle in Huntington. Did you miss our event – check out our television coverage of our Gala!

Where We’re Headed in 2020!

Well, now that we have all this land preserved, it’s time for Long Islanders to get out and enjoy it! We want to make the Pine Barrens a destination, where people across Long Island and beyond seek out, come to and enjoy.

We’re going to be launching a new education, recreation and stewardship initiative. Our goal is to become the leading resource on all things Pine Barrens recreation. This is going to include producing new guides and online resources on how to best enjoy the Pine Barrens – whether that be through hiking, boating, camping, bird watching and more. And we will be leading more guided hikes and other outdoor activities. We’re also going to be hosting educational talks and forums. And we’ll be leading stewardship activities, like trail maintenance and clean-ups.

Yes, we still have a lot of work ahead of us. We’re still going to be continuing our drinking and surface water preservation campaigns and of course, we’ll still be fighting The Lewis Road project this coming year. But, it’s time the people of Long Island enjoyed the Pine Barrens that they worked so hard to protect and we’re going to help them do that!

Thanks for staying with us! We hope you have a fun and peaceful Holiday Season!

By: Katie Muether Brown, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Help us keep helping our environment – make a contribution today!

Posted on December 18, 2019 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

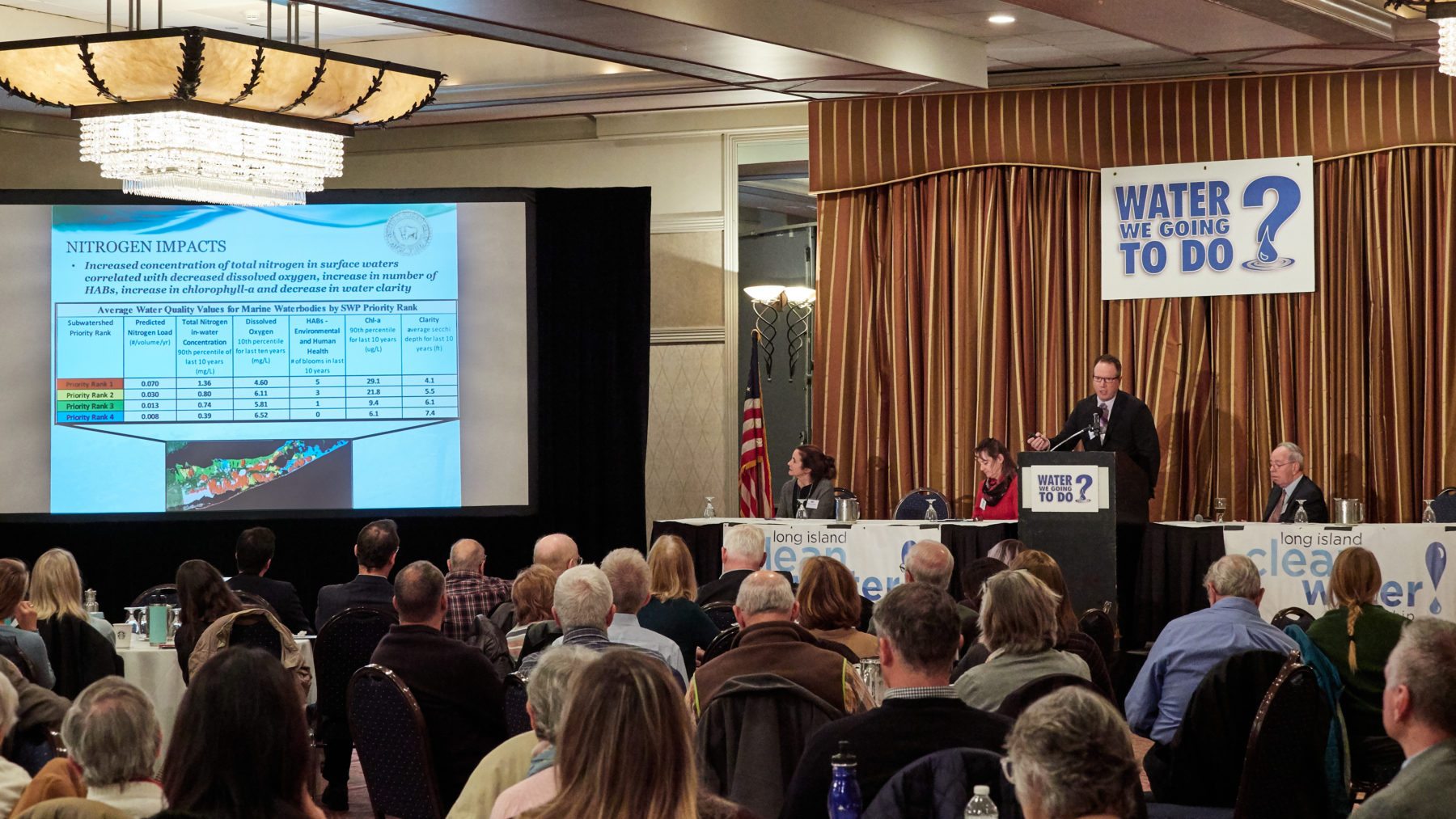

“Water We Going To Do?” – Eighth Annual Conference

On Tuesday, November 19th, the Long Island Clean Water Partnership hosted its eighth annual “Water We Going To Do?” Conference. The Society is a co-founder of the Partnership, along with Citizens Campaign for the Environment, Group for the East End, and The Nature Conservancy in New York.

The conference’s purpose is inform Long Islanders about the progress made toward improving drinking and surface water quality, across Nassau and Suffolk Counties. About 180 Long Islanders came out to hear the latest on the effort to restore our waters. Did you miss it? No worries! We’re here to provide you with a summary.

The State of Our Waters

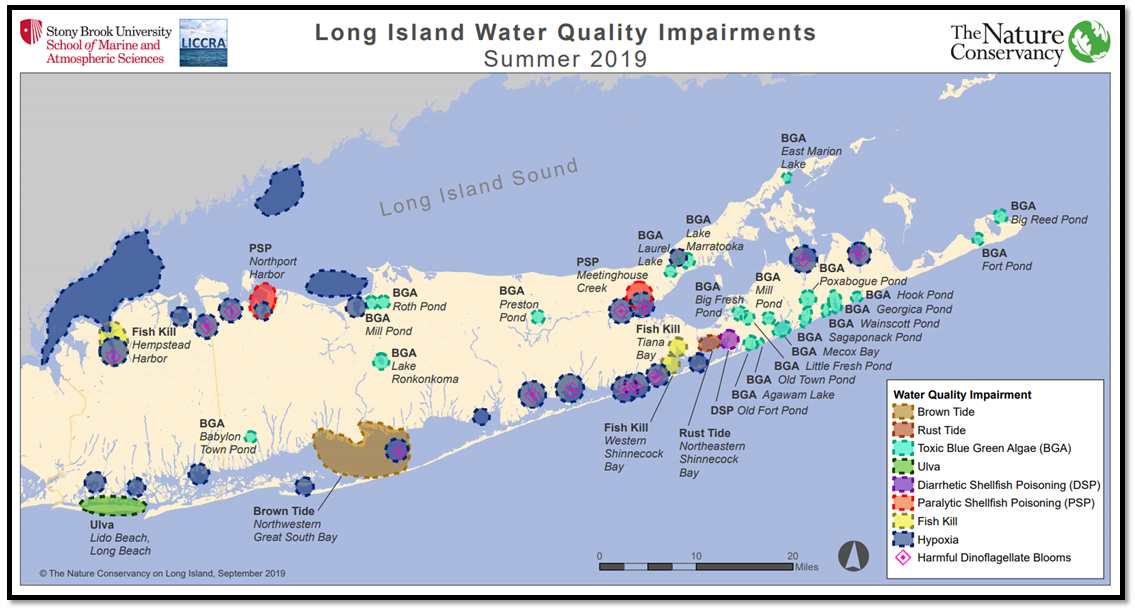

Dr. Chris Gobler of Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, set the stage for the conference by providing an overview of the water quality problems that exist throughout the Island.

Water Quality Impairments Across Long Island- Credit: Dr. Chris Gobler/TNC

Nitrogen pollution, most notably from individual residential cesspools and septic systems, is entering our drinking and surface waters. This excess nitrogen in our waters has led to the proliferation of harmful algae blooms and oxygen-starved waters across Long Island, posing a public health threat, killing marine life, and closing our beaches and shellfish beds.

Dr. Gobler did offer some hopeful insight: There are solutions available that can help us “turn the tide.” New nitrogen-removing septic systems are available, that will greatly reduce the amount of nitrogen entering our waters and consequently, restore our marine ecosystems.

Environmental Achievement Award

Dr. Gobler, on behalf of the Long Island Clean Water Partnership, presented an Environmental Achievement Award to Bill Korbel, the recently-retired meteorologist from News 12 Long Island. Bill Korbel was honored for developing and broadcasting the nation’s first ever water quality reports on a news network. Mr. Korbel worked closely with Dr. Gobler throughout the years, informing Long Islanders of water quality concerns across Long Island, in the summers, before they head to the beach.

Meteorologist Bill Korbel presenting Summer Water Quality Index Reports for News 12 Long Island

Plans to Address Nitrogen in Our Waters

Susan Van Patten from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) provided an update on The Long Island Nitrogen Action Plan (LINAP). LINAP is a joint effort between the NYSDEC and the Long Island Regional Planning Council, a multi-year initiative to reduce nitrogen in our drinking and surface waters. The plan’s current focus is on working with Nassau and Suffolk Counties to create Subwatershed Plans (more on that below), manage fertilizer use, explore water reuse opportunities and establishing “Nitrogen Smart Communities.”

Ken Zegel of Suffolk County’s Department of Health Services and Mary Anne Taylor of CDM Smith, a consultant to the County, provided updates on the Suffolk County Subwatershed Wastewater Plan. (SWP). The SWP, released back in July, measures current nitrogen loads in 180 individual watersheds and determines the amount needed to be removed to recover our ecosystems. Most of the Island’s watersheds will need nitrogen reductions by as much as 90% to improve water quality.

Emerging Contaminants

In addition to nitrogen, harmful and toxic chemicals are also entering our waters and are becoming of increasing concern. These chemicals are called “emerging contaminants.” Adrienne Esposito of Citizens Campaign for the Environment, spoke about 1,4-Dioxane, a synthetic compound found in many consumer products. 1,4-dioxane is listed by the EPA as a “likely carcinogen.”

Common products found to have dangerously high levels of 1,4-dioxane – Credit: CCE

This past legislative session, the New York State Senate and Assembly overwhelmingly passed a bill that would ban 1,4-dioxane from consumer products. Ms. Esposito urged conference goers to call Governor Cuomo’s office and encourage him to sign this important piece of legislation (A.6295/S.4389).

Ty Fuller from the Suffolk County Water Authority, shared some good news about a piece of legislation that did pass and has been signed in New York State. The costs of clean-up and treatment of emerging contaminants such as 1,4-dioxane and PFOS/PFOA is staggering. Mr. Fuller argued that these costs should not fall on the water providers and their customers, and should instead fall on the polluters who contaminated our waters in the first place. This new piece of legislation does just that – it extends the statute of limitations for water providers to sue contaminators to recoup pollution clean-up costs.

The Clean Water Partnership also welcomed special guest, Suffolk County District Attorney, Tim Sini. DA Sini updated the conference on a special investigation his office completed and the results of a Grand Jury that looked into illegal dumping and sand mining. The investigation into illegal solid waste disposal led to an 130-count indictment charging 30 individuals and 9 corporations and an additional 5-count indictment charging one additional corporation. DA Sini discussed the need for new legislation that sets clear statutes related to crimes of illegal dumping and illegal sand mining, and sets harsher penalties to polluters.

Water Quantity & Conservation

Long Island is not only facing water quality problems, but water quantity issues as well. Dr. Frederick Stumm, of the United States Geological Survey, discussed his work on the “Long Island Sustainability Project.” Dr. Stumm noted that in several areas of Nassau County, over-pumping of our drinking water aquifers has led to saltwater intrusion and the closure of public supply wells.

Alan Weland of SUEZ Water discussed several projects to re-use and conserve water at the Cedar Creek Water Reclamation Facility in Wantagh. The new system will preserve up to 300 million gallons of groundwater per year. SUEZ is also looking to implement water reuse systems at the Bay Park and Glen Cove facilities in the future.

Future Actions

The Conference’s final speakers, New York State Assemblymen Steve Englebright and Fred Thiele and Suffolk County’s Deputy County Executive for Administration Peter Scully, all agreed on the same point: We have made significant progress, but there is still a lot more we need to do. We’re at a critical point in the campaign. We know what the problems are. We know how to fix them. Now, we need to implement the solutions. There are new septic systems that remove nitrogen. Next, we need to figure out a way to finance the replacement of 360,000 septic systems across Suffolk County. This cost should not fall on the homeowner alone. We need to create a dedicated recurring revenue stream to provide grants and low cost loans to homeowners who wish to assist homeowners with replacing their old systems with new nitrogen-removing technology. This will be the Long Island Clean Water Partnership’s focus in the coming year.

The Pine Barrens Society will cover the conference on its television program in early 2020. Stay tuned!

By: Katie Muether Brown, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Posted on November 22, 2019 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Halloween in the Long Island Pine Barrens

Looking for ghosts, bats, and other spooky things this Halloween? Look no further than the Long Island Pine Barrens!

Pay a Visit to Long Island’s Ghost Forest!

Take a trip to the 1815 acre Hubbard County Park in Hampton Bays to visit Long Island’s own “Ghost Forest.” After walking through the woods, you will come out to the shoreline along Flanders Bay. Here, at low tide, you will see tree stumps from Atlantic White Cedars that had thrived centuries ago when sea levels were lower. Not only are these trees an interesting sight to see, they are extremely rare!

Hubbard County Park “Ghost Forest” – Sandy Richard

Hubbard County Park “Ghost Forest” – Sandy Richard

Keep an Eye Out for The Ghost Plant!

When walking along in the Pine Barrens, keep an eye out along the forest floor for the “Ghost Plant” or “Indian Pipe.” Because of its white color, the Indian Pipe is often confused as a fungus, but it’s really a flowering plant. The plant is white because it doesn’t have any chlorophyll. Since it doesn’t have any chlorophyll, it doesn’t photosynthesize its own food. Indian Pipes are parasitic and obtain their energy from their host, the mycorrhizal fungus that grows on tree roots.

Indian Pipe or Ghost Plant – KM Brown

Watch Your Fingers & Toes!

As covered in a previous blog, the Long Island Pine Barrens is home to its own Little Shop of Horrors! No, you won’t find any Venus Fly Traps that crave human blood, but you will find three other special types of carnivorous plants. They are the Pitcher Plant, Sundew, and Bladderwort. These plants get their nutrients mostly from consuming animals, and are commonly found in habitats with poor soil conditions, where they cannot rely on the ground to obtain their essential nutrients of nitrogen and phosphorus.

Pitcher Plant – Sandy Richard

Fang-tastic Bats!

There are about seven common bats found on Long Island: Little Brown Bat, Tri-colored Bat, Big Brown Bat, Northern Long-eared Bat, Eastern Red Bat, Hoary Bat and the Silver-haired Bat. Bats are a crucial part of our environment! They play a critical role in controlling insect pests. A single little brown bat can catch more than 1,000 mosquito-sized insects in one hour! They also pollinate plants and disperse seeds. If we lose bats, we lose our natural pest-control – increasing our demand for chemical pesticides that harm our ecosystems even further. Now that’s a scary thought!

Little Brown Bat

The Scariest of All!

Do you know what’s the scariest sight to see in the Pine Barrens? Areas where people have illegally dumped refuse or destroyed our precious ecosystem with illegal ATV use. Illegal dumping and All-Terrain Vehicle (ATV) use severely threaten the Pine Barrens! Sadly, there are people that dump household trash, business garbage, yard waste and even junk cars. Dumping yard waste in the woods can introduce threatening non-native species to the Pine Barrens. The use of ATVs scares wildlife, destroy plants and nature trails, ruins the soil and can increase the risk of wildfire. ATVs are NEVER legal on public lands and roads. Be a guardian of the Pine Barrens and report a violation immediately when you see it by calling 1-877-BARRENS.

Illegal Dumping in the LI Pine Barrens – Sandy Richard

ATV Damage in the LI Pine Barrens – Sandy Richard

Happy Halloween! You never know what you will find in the Pine Barrens woods! Enter if you dare.

By: Katie Muether Brown, LI Pine Barrens Society

Posted on October 30, 2019 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

How Humans Have Shaped the Long Island Pine Barrens

By: Katie Muether Brown (originally published in The Pine Barrens Today Vol. 32, No. 2)

The origin of the Long Island Pine Barrens has often been debated. The vegetation in the Pine Barrens thrives due to the acidic, nutrient-poor and dry soil composition common to Central Long Island. However, by studying the historical spatial changes of the area, it is apparent that humans have had a great influence in shaping the Pine Barrens that we all know and love today. Human disturbance throughout the past three hundred years, such as logging,

land clearing and fire, have promoted the growth and expansion of Pine Barrens vegetation. Pollen records, charcoal profiles, early maps and records help provide the evidence.

Today, while walking through the Pine Barrens, one expects to see native vegetation such as pitch pines, scrub oak, blueberry, huckleberry, grasses and forbs. However, if one stepped back in time, a couple centuries ago, the landscape would be drastically different from today. What we know as the “Pine Barrens” today, was previously dominated by tree oaks, American chestnuts and other deciduous hardwoods. Pitch pine and scrub oak were present back then, but in much smaller numbers than today. The vegetation of the area changed to its current state some 200 years ago, due to an increase in human-caused disturbance.

Euro-Americans began settling on Long Island in the mid-17th century and thus began the disturbance of an ancient environment. This involved extensive land-clearing and the establishment of a logging industry, using wood for building, fuel and shipbuilding. Wood was exported to New York City and other surrounding areas. In the year of 1812 alone, Brookhaven Town exported over 100,000 cords of wood. Hardwood trees (dominant in the area at the time) were preferred over pitch pines for fuel and cooking because they burned evenly and produced less soot. Large tracts of land across central-eastern Long Island were left barren, stripped of their primordial hardwood vegetation due to logging and brush removal. This heavy removal of hardwoods during the first few centuries of Long Island’s establishment provided an opportunity for the shade-intolerant pitch pine and scrub oak to expand in numbers.

The pollen record for Deep Pond (Wading River, NY) has been studied to help examine this change in vegetation and to determine its causes. Pollen profiles were taken by examining levels of pollen trapped deep in pond sediments. Pre-settlement pollen levels account for only 15% of pitch pine and around 50% for oak. These profiles show that pitch pine pollen levels increased dramatically after Euro-American settlement began and that tree oak pollen levels decreased. The clearing of hardwood trees that began with human settlement allowed the shade-intolerant pitch pine to take root.

Fire frequency and intensity also increased with early Long Island settlement. Almost all fires (90%) at this time had human causes. Fires were commonly used for land clearing (burning brush) and for cooking. The establishment of the Long Island Railroad was also a great source of fire during this time. Fires were started by sparks and by hot embers dumped along the tracks. With little or no means of fire suppression, these fires quickly expanded and often burned for weeks at a time. In 1862, one fire was so extensive, that it started in Smithtown and swept all the way into Southampton — essentially burning the entire middle of the island. By the year 1911, the Pine Barrens were burned so much that the area was seen as unproductive and untaxable.

Charcoal profiles have also been studied in Deep Pond. Sediments were examined for varying levels of charcoal within the sediment over time. Charcoal levels almost doubled after settlement. An increase in fire-frequency favored the establishment of the pitch pine. Pitch pines are more adapted to fire than tree-oaks, with thick bark and serotinous pine cones, protecting the seeds from the fire and only opening and releasing seeds after the fire. Oaks also have a longer fire-return interval, taking them longer to return after a fire has burned the area. Pitch pines are dependent on fire (and other disturbances) in order to maintain their dominance over hardwoods.

Pitch pine-oak-heath woodlands and pitch pine-scrub oak barrens expanded so much after Euro-American settlement that they stretched as far west as Hicksville and Farmingdale. Some of these woodlands also covered large sections of Central Park.

Looking again at the pollen profiles for Deep Pond, we see that after 1920, pitch pine began to decline and scrub oak gradually reestablished itself as the dominant tree. This is mainly due to a lack of disturbance, including a flagging logging industry and the development of fire suppression methods. Without fire, oaks and other hardwoods will gradually replace the pitch pine in dominance. In the future, development is not the only threat to our precious ecosystem; fire suppression is also an important threat to these complex plant communities.

Adapted from: Kurczewski, Frank E., and Hugh F. Boyle. “Historical Changes in the Pine Barrens of Central Suffolk County, New York.” Northeastern Naturalist. 7.2 (2000): 95-112.

Posted on September 11, 2019 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Long Island’s Little Shop of Horrors

By: Katie Muether Brown, Long Island Pine Barrens Society

The Long Island Pine Barrens is a special place. Our Pine Barrens boast the greatest diversity of plants and animals anywhere in New York State. It is home to literally thousands of plants and animal species.

The Long Island Pine Barrens is also home to its own Little Shop of Horrors! No, you won’t find any Venus Fly Traps that crave human blood, but you will find three other special types of carnivorous plants. They are the Pitcher Plant, Sundew, and Bladderwort. These plants get their nutrients mostly from consuming animals, and are commonly found in habitats with poor soil conditions, where they cannot rely on the ground to obtain their essential nutrients of nitrogen and phosphorus.

Pitcher Plants

Pitcher Plants are also known as the “Soldier’s Drinking Cup.” Because of the plant’s ability to retain water for weeks and its unique pitcher or cup shape, it is believed that soldiers centuries ago, used to drink out of Pitcher Plants on long trips.

Insects are attracted to the mouth of the pitcher that contains a trail of nectar-secreting glands that extend down the walls of the plant. The inside walls of the pitcher also have downward facing “hairs,” which make it difficult for the insect to climb back up out of the plant. Once the insect has landed at the bottom, the plant drowns the insect in a liquid that contains digestive enzymes.

Pitcher Plant by John Brandauer (Flickr CC)

Pitcher Plant – Sandy Richard (Flickr CC)

Sundews

There are two types of sundews that exist in the Pine Barrens – thread-leaved and spatulate-leaved sundews. These plants have sticky “tentacles” that capture and enfold prey and exude digestive juices to make a meal of them. Once the insect is consumed, they will then unravel their tentacles.

Thread-leaved Sundew – Sandy Richard (Flickr CC)

Spatulate-leaved Sundew – Sandy Richard (Flickr CC)

Bladderworts

Bladderworts are known as the fastest plant in the world! Bladderworts are an aquatic carnivorous plant. There are about 200 known species of bladderworts that exist in the world, but there are only about a half a dozen that are native to Long Island. Bladderworts feed upon small animals, primarily tiny crustaceans. Each plant contains dozens and sometimes hundreds of tiny bladders that float in the water. Each bladder is a “snap trap” that opens up in response to movement – drawing an animal in and then digesting it.

Check out this video that shows the Bladderwort in action!

There’s more than meets the eye in the Pine Barrens. Next time, while you’re on a hike in the Barrens, slow down and take a closer look at the magic that surrounds you. Just make sure to keep your fingers and toes safe from some hungry plants! 😉

Posted on August 14, 2019 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

The Pine Barrens: It Ain’t Just Pines

By Patricia Pelkowski, The Nature Conservancy

In broadest outline, Long Island’s natural communities historically consisted of two bands of hardwood forest (a broad band covering the Harbor Hill and Ronkonkoma moraines in the northern portions of the island, and a narrower band along much of the south shore) bordering grasslands in Nassau and western Suffolk counties and pine barrens further east. While all of these habitats were significantly impacted by rapid development following World War II, none were hit harder than Long Island’s grasslands.

Before they were lost to development, two distinct grasslands were prominent features of Long Island’s natural landscape. The Hempstead Plains, at one time the largest prairie east of the Mississippi River, covered over 60,000 acres (nearly 100 square miles) of central Nassau County, stretching from the Queens border to modern day Plainview. Today, less than 100 acres of this prairie ecosystem remain, scattered among several small parcels in the vicinity of Nassau Coliseum and Eisenhower Park. At its eastern border the Hempstead Plains merged into the Oak-Brush Plains, a transition zone in which prairie grasses intermingled with islands of pitch pine and scrub oak, the dominant trees of the more easterly pine barrens. Naturalists estimate that 95 percent of the Oak Brush Plains, which at one time reached eastward nearly to the Connetquot River, have been lost. Sizeable remnants of this habitat can only be found at the Edgewood Oak-Brush Plains Preserve and the nearby Pilgrim State Hospital. Loss of these grasslands contributed to the extinctions of birds such as the Heath Hen and Eskimo Curlew, as well as local extirpations of numerous other plant and animal species.

Interestingly, the soils underlying these former grasslands are very similar to the soils beneath the pine barrens, causing biologists to wonder why some areas became grasslands while others grew into pine barrens. While this question is still not fully resolved, it appears that fire played a major role in making these determinations. Prairies can tolerate yearly fires, a burn frequency which is too great for pitch pines and other tree species. Accounts from early settlers indicate that fire was indeed a nearly annual occurrence in the Hempstead Plains. In many cases these early settlers suppressed fires whenever possible, resulting shortly thereafter in the encroachment of trees and shrubs into portions of the plains.

Despite their name, the pine barrens are neither barren nor a monoculture of pines. To the contrary, the pine barrens are a rich matrix of softwood forests, ponds, bogs, swamps, and grasslands. In fact, most of the remaining grasslands on Long Island are located within the pine barrens, although they are often overlooked by the casual observer. As with all other habitats within the pine barrens, grasslands contribute significantly to the overall species diversity of its parent ecosystem, supporting a wide range of specialized plant and animal species which are dependent upon this habitat. Unlike many other habitats, however, grasslands are at risk both from human encroachment and from natural processes occurring within the pine barrens. Grasslands are an early successional community, and if left undisturbed will eventually be colonized by shrubs and trees, eventually leading to its further succession into a forest-type habitat. As noted earlier, the longevity of the Hempstead and Oak-Brush Plains was almost certainly due to frequent disturbance by fire, which prevented encroachment by woody plants.

Due in large part to the vulnerability of grasslands to both human and natural activities, grasslands are the most rapidly declining habitat within the northeastern United States. Not unexpectedly, comparable declines are seen in many species of grassland-nesting birds such as Bobolink, Eastern Meadowlark, and Vesper and Grasshopper Sparrows, as well as in several moth and butterfly species. Not surprisingly, on Long Island remnant populations of many of these species can only be found at a few isolated grasslands within the pine barrens.

Due to its vulnerability to natural succession, grasslands cannot be preserved by acquisition alone. Rather, this habitat requires careful stewardship and ongoing management to preserve its viability as grassland and prevent its development into shrubby and ultimately forested habitats. Toward that goal, in the next year The Nature Conservancy will be undertaking an ambitious project to inventory all remaining grasslands within the Pine Barrens. With such an inventory completed, we will be able to develop appropriate management programs and agreements for these parcels, ensuring that the grasslands of the Pine Barrens, unlike their western brethren, will remain a vibrant part of Long Island’s ecosystem in the years to come.

Posted on July 17, 2019 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

This Place, Long Island

By John Turner, Pine Barrens Society Co-Founder

Paradise Found:

This place, Long Island, with its basement of 450 million year old shist bedrock dating back to the Silurian Period of the Paleozoic Era; a time when the land was first invaded by vascular plants, when the first jawed fishes plied primordial oceans;

This place, Long Island, where along the base of its North Shore bluffs ooze cretaceous clays containing leafy imprints of trees a Long Islander would hardly recognize — cinnamon, magnolia, gingko, eucalyptus, sequoia, and fig trees — imprints in materials laid down in a vast delta upon the basement of bedrock from the eroding Appalachian Mountains;

This place, Long Island, a million acre sandbox on permanent loan from New England, sculpted by two continental ice sheets, 500 feet high along their moving fronts, pocked by kettleholes, rounded by kames and moraines, with two bony fingers that jut into the briny foam wash of the Atlantic;

This place, Long Island, whose outwash plain during the ice age extended to the edge of the continental shelf, where rushing braided streams fed from the melting ice sheets cascaded as waterfalls into the lowered Atlantic;

This place, Long Island, with its hidden, underground aquifers more than a thousand feet deep, containing incomprehensible amounts of water – 70 trillion gallons- enough to fill all of Manhattan Island to the height of the top of the Empire State Building; if you thirst is quenched from the Lloyd aquifer, the deepest one, you’re drinking water that fell from rain clouds that formed a thousand years before the birth of Christ;

This place, Long Island, home thousands of years ago to species of the boreal forests – red spruce, arctic willow, and crowberry, and mastodons — yes, mastodons!– whose sets of molar teeth have been unearthed by bottom draggers fishing the Atlantic. And maybe, just maybe, the skies over Long Island during this time held the shadows of California condors, whose bones have been found within caves in eastern New York;

This place, Long Island, that in 1609 Robert Juett, who was Henry Hudson’s first mate, exclaimed as his ship, the Half Moon, slipped in New York Harbor, “we found a land full of great oaks, with grass and flowers, as pleasant as ever has been seen.” Daniel Denton, 61 years later had this to say, “The greatest part of the Island is very full of Timber, as Oaks, white and red, Walnut-trees, Chestnut-trees, which yield store of mast for swine…also Maples, Cedars, Saxifrage, Beach, Birch, Holly, Hazel, with many sorts more…the Countrey itself sends forth such a fragrant smell that it may be perceived at Sea before they can make the land.”

This place, Long Island, where the plaintive echoes of the Eskimo Curlew once ringed across unbroken expanses of salt marsh and whose forests filled with the howls of timber wolves and the whistling of wings from countless passenger pigeons and whose thickets of scrub oak echoed with the booming mating calls of the heath hen;

This place, Long Island, which once knew Black bear, mountain lion, beaver, cricket frogs, and timber rattlesnake;

This place, Long Island, saw the last known Labrador duck pass through the veil of extinction, as a young male mortally wounded by a gunner, crashed into the wavelet waters of the Great South Bay in 1875;

This place, Long Island, was once the osprey capital of the world with more than one hundred of the their jumble stick nests on Gardiner’s Island alone and an estimated 2,000 nests on eastern Long Island;

This place, Long Island, boasted the largest prairie east of the Mississippi River; it is still called the Hempstead Plains but it is a tiny, tiny fragment of the sea of grasses that once graced central Nassau County and gave rise to the communities of Plainedge and Plainview; and the Plains merged with the dense shrubby oak thickets of the Oak Brush Plains at a place later to be called Island Trees – where islands of pitch pine stood surrounded by prairie grass;

This place, Long Island, where hessel hairstreak butterflies once danced in the shadowy swamps of atlantic white cedar lining tea colored streams which drained the interior pine forests that provided water to productive cranberry bogs that made Suffolk County the third largest cranberry producing area in the US a century and a half ago;

Paradise Reduced:

This place, Long Island, with the all but 40 acres of the Hempstead Plains gone, to make way for modern day suburbia that spread post World War II and where 95% of the coastal salt marshes fringing Nassau County’s South Shore have been filled or bulkheaded;

This place, Long Island, where half of the Pine Barrens have been lost, where more than half of our fertile farmland is gone, and where a suite of invasive plant species – like purple loosestrife, Asiatic bittersweet, Japanese knotweed and barberry, garlic mustard, and porcelainberry – threaten the ecological integrity of the places we care about;

This place, Long Island, where 2.6 million Long Islanders work, live, and play above their water supply and due to this unique relationship have a groundwater system degraded by contamination from a host of chemical acronyms enough to make the makers of alphabet soup proud

Paradise Redux:

And while diminished, this place Long Island today still provides home and hotel accommodations to more than 300 species of resident and migratory birds, some of which are hemispheric globetrotters passing through on their magical journeys that connect their breeding and wintering grounds (it reminds me of the classic surfing movie in search of perpetual summer); a spectacular example is the blackpoll warbler, which in breeding plumage is reminiscent of a black-capped chickadee. In the fall the overwhelming majority of individuals of this species, which weight less than an ounce, move east to the Canadian Maritimes, New England and Long Island, some having flown as much as 3,000 miles from Alaska. And then in a 2,300 mile leap of faith these feathered puffs, (as one writer has noted you could mail one using a single postage stamp) launch out in favorable weather conditions (a high pressure system with winds from the northwest) into the hostile Atlantic. At first they head to the southeast staying the course until about Bermuda where they pick up the trade winds that redirect them to the southwest making landfall typically in Venezeula or Guyana some 72 hours later. That’s right folks after lifting from LI they fly non–stop for as much as three days straight. During this time they will have flapped their wings an estimated 3 million times, never more than a second or two rest between flaps, and as one researcher noted if they burned gasoline instead of stored fat they would get about 720,000 miles to the gallon.

This place, Long Island, whose coast still offers nurturing habitat for dozens of beach dependent species including piping plovers – 62 new youngsters growing up on Southampton beaches this year alone – tens of thousands of sea beach amaranth Amaranthus pumilus, a modest plant if ever there was one and where earlier this year at Orient Point State Park seabeach purslane Sesuvium maritimum was rediscovered after an absence of 90 years;

This place, this crowded Long Island, still boasts whales frolicking off shore and harbor seals onshore and where at the mouth of the Peconic Bay harbors large rafts of sea ducks in the winter – the vocal long-tailed ducks with their bubblegum-pink bills, the red-breasted mergansers with their punk rocker haircuts, and the countless number of stout-bodied scoters – white-winged scoters, the clownish surf, and the not so common common scoter; one flock of scoters I counted, more than a decade ago, from the pavilion at Montauk Point State Park contained 35,000 birds and where last winter I was privileged to watch as a thousand gannets dropped like torpedos from 100 feet, sending up ten foot plumes, as they participated in a full-fledged feeding frenzy preying on a school of herring estimated to contain 400 million fish;

This place, Long Island, which still boasts nearly three dozen species of native orchids. And lurking in the wetlands, now pull in your fingers and toes – are plants that eat animals – more than half a dozen bladderworts, the umistakeable pitcher plant and three species of sticky sundews; beautiful but deadly!;

This place, this crowded Long Island, still harbors tigers in the night, as in tiger salamanders; if you doubt this go then on a warm and dank late winter night when the scent of pine is strong and you can watch these magnificent ambystomid salamanders – the mole salamanders as charismatic as any amphibian can be – engaged in an eons old urge to reproduce as they crawl down to their vernal ponds in search of a mate;

This place, this crowded Long Island, still harbors tigers in the night, as in tiger salamanders; if you doubt this go then on a warm and dank late winter night when the scent of pine is strong and you can watch these magnificent ambystomid salamanders – the mole salamanders as charismatic as any amphibian can be – engaged in an eons old urge to reproduce as they crawl down to their vernal ponds in search of a mate;

This place, Long Island, where the striped skunk hangs on by its fingernails and the gray fox by the tips of its fingernails;

This place, Long Island, whose citizens led the successful fight to end the DDT madness, who passed a county bottle bill which catalyzed a state bottle law, who banned sudsy detergents, who have voted for 19 out 20 ballot measures to protect land, and who dedicated its four rivers to the state’s river protection program; whose bays and estuaries – the Peconic Bay, Moriches and Great South Bay, and LI Sound are the focus of curative measures to restore their ecological health and vitality;

This place, Long Island, which has spent more than a billion dollars to protect its wild places and open spaces and has the only federally designated wilderness area in New York State – on that most fragile and dynamic strand of sand called Fire Island – this in a state that boasts the Adirondack and Catskills forest preserves;

This place Long Island, reaching from the shadow of the great metropolis, has protected nearly 105,000 acres of land in the Pine Barrens; a big enough place for you to get lost in the woods, large enough for you to be able to walk from Rocky Point to the Shinnecock Canal, your feet never leaving public parkland, that’s your land and that’s my land; and it’s the land of the prairie warbler and Mr. Drink-your-tea.

This place Long Island where on the 13,000 acre Montauk Peninsula, from the Napeague strip east, two-thirds of all the land is publicly-owned parkland;

Here on Long Island we have lost much but we achieved so much. Perhaps we needed loss to understand what we wanted to gain. So let’s give due to the great and lasting work of Long Island’s great conservationists and naturalists – people such as Dennis Puleston, Gil Raynor, Roy Latham, Leroy Wilcox, Edwin Way Teale, and Robert Cushman Murphy who was the first to advocate for the establishment of a Pine Barrens preserve “urging governmental officials to make it a really big preserve”. Let’s appreciate the ongoing and tireless efforts of folks like Paul Stoutenburgh, Art Cooley, Jim Tripp, Steve Englebright, Dick Amper, Marilyn England, Dan Morris, and many, many others. Most importantly, let’s continue to marvel at and revel in the magic of the natural world as it unfolds around us, in infinite variety and expression every day.

Like ripples in a pond caused by a tossed pebble let’s carry our efforts forward and outward to convince others to protect those places so special to us and lets continue to reveal to our fellow Long Islanders by informing, educating and advocating, and most of all celebrating, the very special natural treasures that collectively comprise Long Island.

Like ripples in a pond caused by a tossed pebble let’s carry our efforts forward and outward to convince others to protect those places so special to us and lets continue to reveal to our fellow Long Islanders by informing, educating and advocating, and most of all celebrating, the very special natural treasures that collectively comprise Long Island.

Fill your pockets deeply with pebbles and toss often.

Posted on June 17, 2019 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society

Spring in the Pine Barrens

By Bob McGrath, Pine Barrens Society Co-Founder

The natural world that surrounds us offers thousands of simple pleasures – the splendor of fall foliage, the subtle fragrance of Trailing Arbutus, the tranquil song of the Wood Thrush, the uncanny rhythm of nature’s breadth and grandeur – if only we take the time to stop, listen, and reflect. For me, enjoying nature’s pleasures is a natural and harmonious choice and there is no better time to slow down and take in all that the natural world has to offer than the onset of spring in our Pine Barrens.

Spring for me doesn’t simply arrive (as it officially will this year when the clock strikes 1:48 AM on March 20th), with one single event, but rather with a series of events like the first soaking rains of the New Year. This year that occurred in January and with them came the first sign that spring was in the air, the emergence of Tiger Salamanders. Those who have ever trekked-out into the night in search of these mysterious denizens know full well the feeling of renewed spirits that comes over you when you watch as the spatula-tailed males court females by conducting what could best be described as a water ballet. Tigers are not the only mole salamander to go through such elaborate courtship rituals; in fact, two other of Long Island’s four mole salamander species (the Spotted and Blue-spotted) have similar breeding habits. Yet it is the Tiger that makes its emergence first, often before the ice has melted from their breeding ponds and often before any of us is really thinking about the onset of spring.

On many of these journey’s I have often encountered another sure sign that spring is on its way, the territorial calling of our largest resident owl, the Great Horned. Like Tiger Salamanders, Great Horned Owls begin breeding early in the season, often setting up territories in early January and incubating eggs by mid-February throughout not only our Pine Barrens but in mixed deciduous forests as well. Just last week I happened upon a female as she sat hunkered down in an old gray squirrels nest almost certainly incubating this year’s clutch of eggs. She is actually somewhat late I thought to myself as she leered intently at me.

As we move through March, another delightful sign that spring is indeed in the air in our Pine Barrens is the arrival of Pine Warblers. One of a good number of Warbler species that calls the Pine Barrens home, the Pine is first to arrive from it’s wintering grounds in the southern United States. For me their subtle trill can warm even the chilliest March morning as they search the tops of Pitch Pines looking for winter moths to feed upon.

A walk through the Pine Barrens in spring also brings with it numerous wildflowers that if you do not get out early to see will be gone until next year. Although not considered true ephemerals (species that capitalize on early spring sunlight by blooming in profusion, setting seed and dieing back, often by mid June) species such as Bearberry, Trailing Arbutus, and Birds-foot Violet are just a few of the wildflowers that one can encounter. The first of these to bloom is Bearberry, the ubiquitous groundcover found throughout the Pine Barrens. Bearberry is actually an evergreen shrub that many people do not even realize has a flower as they begin to make their appearance in late March and early April long before most other species begin to stir. A member of the blueberry family, bearberry has a small white, bell-like flower that often is laced with delicate hues of pink. As it is one of the first flowers to appear in spring, it is often host to many of the Pine Barrens early spring species of butterflies such as the Brown Elfin and Spring Azure Blue. If you are looking to enjoy the beauty of Bearberry the coming weeks is the time to do so.

Yes, spring in the Pine Barrens truly is a time for rekindled spirits. To me, it the chorus of Spring Peepers, the first calls of Whip-poor-wills in mid-April, Eastern Bluebirds returning to nesting boxes in Calverton, and the “peenting” of American Woodcocks in the secondary fields of Connetquot River State Park. It is a cold spring shower, a gathering of Tree Swallows on a coastal plain pond, the tranquil sunset over the Manorville Hills. Spring in the Pine Barrens is like old friend. It is the renewal that I look forward too each year once we move from November into December. The Oak Brush Plains I hiked through with two good friends as a teenager, The Dwarf Pine Plains I fell in love with as a teacher during the eighties, and the vernal ponds I have spent countless hours at in during middle of night looking for signs that Tiger Salamanders have emerged once again.

It’s been arriving now for weeks if we only take the time to stop, listen, and reflect.

Posted on May 21, 2019 by Long Island Pine Barrens Society